Introduction to the English Bible

Translation

The

translation of the Bible from its original languages

(Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek), is a complex story. The

process of translation for each language is story in

itself. As the Gospel spread to other lands, the books of

the Bible, both Old and New Testaments were also translated,

some earlier then others.

The

translation of the Bible from its original languages

(Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek), is a complex story. The

process of translation for each language is story in

itself. As the Gospel spread to other lands, the books of

the Bible, both Old and New Testaments were also translated,

some earlier then others.

The English translation compared to other

translations is a relatively late translation. The story

of the English Bible in many ways is similar to the other

translation stories. To under the translation process, the

student needs to be familiar with history and source

documents behind the translation.

Most readers of the English Bible today, are not

aware of the dramatic story behind the book they hold in

their hand. How a collection of books written in Hebrew,

Aramaic and Greek changed Europe and especially England is

taken for granted by many Christians.

By using the story of the English Bible, we can

see how religion, politics and intrigue each played their

part. Although each translation story is unique, each story

involves a process, how a group of people received God’s

Word in their own tongue.

Other Translations

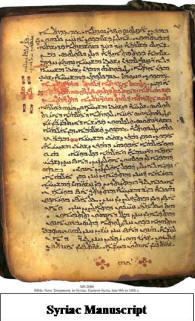

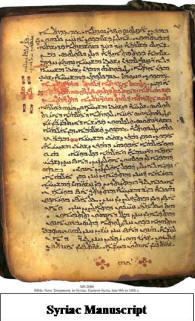

Syriac Versions

The Syriac translation is the Aramaic

translation of the New Testament. The Gospel has an early

history in this region of the world; Antioch and Jerusalem

were the first centers of Christianity. From Syria,

according to Eusebius, an early an early missionary named

Pantaenus in about A.D. 180, took the Gospel to India and

found one of the apostles, Bartholomew had preceded him,

leaving the Gospel of Matthew in Hebrew or Aramaic letters

(Eusebius HE 5.10.2-3).

Prior to the New Testament, the Old Testament

had already been translated into Aramaic in the Jewish

Targums. One of earlier known translations to Syriac is

Tatian’s work called the Diatessaron, meaning through

four. Tatian’s translation was a harmony of the four

Gospels. Tatian founded a group of ascetics in Mesopotamia

called the Encratites who were vegetarians, did not

marry and did not drink alcohol. His views caused his

translation, the Diatessaron to be tainted, for example,

John the Baptist ate milk and honey as opposed to Locust.

The marriage of Joseph and Mary is not mentioned in Matthew

1:18-19.

In the fifth century, the Bishop of Edessa,

Rabbula (411-435) established the Syriac Peshitta. Theodoreus,

bishop of Cyrrhus near the Euphrates (423-457) collected and

removed Tatian’s harmony, Diatessaron, and replaced it with

four separated Gospels.

Coptic Versions

The Coptic language is the language of Egypt, as

opposed to Greek, which was introduced by the armies of

Alexander the Great (333-323 B.C.) and Arabic which the

armies of Islam introduced in the 7th century.

There are two main dialects of Egyptian

Sahidic (Upper Egypt) and Bohairic (Lower

Egypt). The Coptic script is based on the demotic script,

which was derived from the hieroglyphic script.

The Old Testament translation is based on the

Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament. The

New Testament is based on a translation from the Alexandrian

text.

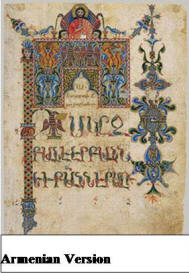

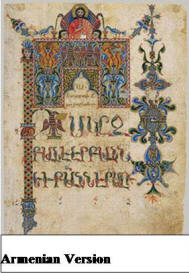

Armenian Version

Next to the Latin Vulgate, the Armenian translation of the

Bible has the greatest number of manuscripts, 1,244 numbered

completely or in part. The Armenian version was produced in

the 5th century an Armenian priest, Mesrop

Mashtotz (361-439) who developed the thirty-six letter

Armenian alphabet. Prior to this, all the books written were

in either Greek or Syriac (Aramaic).

The source of the Armenian Bible’s translation

is the Septuagint for the Old Testament and the Syriac

Peshitta.

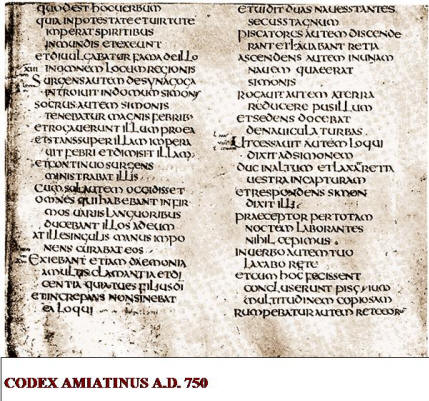

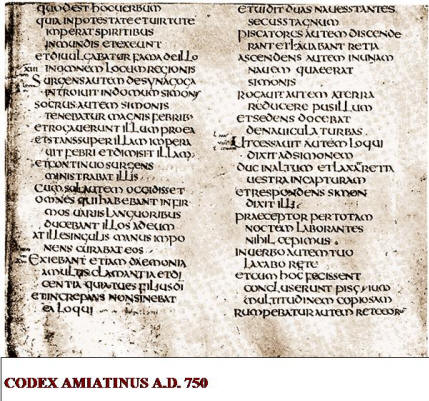

Old Latin

Before St. Jerome’s translation, the Latin Vulgate, the

Bible in Latin was termed Old Latin. By A.D. 250, Latin was

the language of the Christian scribes and clerics, creating

a need for a Latin Bible. The translation of the Bible into

Old Latin varied among the different versions. These

variations caused Pope Damasus I (345-420) to ask St.

Jerome, a Latin and Greek scholar to revise the Latin

translation of the Bible.

Latin Vulgate

Jerome was commissioned by Pope Damasus I to

revise and standardize the Old Latin version. His

translation became known as the Latin Vulgate, which became

the standard of the Catholic Church for 1000-years after its

completion. By A.D. 383, Jerome completed his translation of

the four Gospels based on the Old Latin, but compared to the

Greek text.

Jerome later translated the Old Testament

directly from the Hebrew, this was completed in 405; his

basis of translation was sense-for-sense rather then

word-for-word. Jerome received a great deal of

criticism because he translated from the Hebrew Old

Testament rather then from the Septuagint.

English Translations

Rome conquers the British Isles

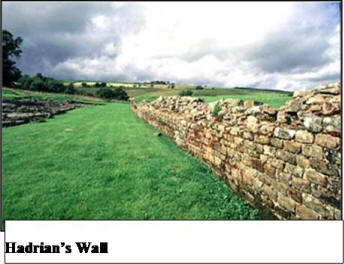

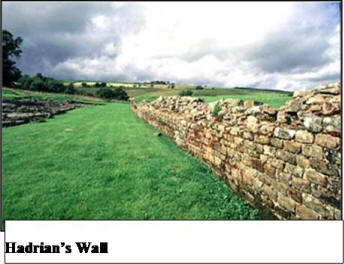

The history of the King James Bible starts with

the history of England. The first written record of

England begins with the Roman conquest dating back to the

time of Julius Caesar in 55 BC, recorded in his “Gallic War

commentaries”. He describes his conquest of England with

more then 800 ships. The Celts made peace with Caesar, this

allowed him to leave and manage Gaul (France). This peace

between England and Rome lasted until the reign of the

Emperor Claudius. Rome invaded with 40,000 soldiers and

established its control over the British Isles in A.D. 43.

England became part of the Roman Empire. Today, Hadrian’s

Wall (117-138) marks the northern boundary of Roman

territory.

Christianity in England

With the spread of Christianity in the Roman Empire,

Christianity became the faith of England by the 3rd century,

as missionaries brought the Gospel to the outer parts of the

Empire.

The church in England was well enough established by the

4th century to send three British bishops—of Londinium

(London), Eboracum (York), and Colonia Linum (Lincoln)—to

the Council of Arles (in modern France) in 314. However,

there is no record of the Bible’s translation into the

English language at this point. Latin was the language of

Rome and its various outposts, including England.

The church in England was well enough established by the

4th century to send three British bishops—of Londinium

(London), Eboracum (York), and Colonia Linum (Lincoln)—to

the Council of Arles (in modern France) in 314. However,

there is no record of the Bible’s translation into the

English language at this point. Latin was the language of

Rome and its various outposts, including England.

The Romans withdrew from England in the 5th

century to save the capital, Rome, from invading Germans

tribes. German tribes also invaded the British Isles, two

tribes, the Angles and Saxons swarmed from Germany, in the

process Christianity almost vanished from the Isles. The

Angles and Saxons, German tribes from Saxony; eventually

merged with the Celts and became known as the English.

For the next 1000 years until the time of Henry

VIII (1491-1547), England was part of the Roman Catholic

Church. The Roman Catholic Church dominated both the

political and religious spheres of nations. During this

period portions of scripture were translated in by various

people, Caedmon (A.D. 678) a cowherder turned scripture into

Old English poems, allowing people to memorize and sing

scripture. Aldhelm ( A.D. 709) the bishop of Sherborne,

translated a portion of the Psalms from the Vulgate into

Anglo-Saxon.

Bede, the father of English history, (A.D. 675-735)

translated the Gospel of John into English on his deathbed.

No portion of this translation remains. Alfred the Great

(A.D. 849-901) was a literate king of Wessex from 871, he

encouraged Christianity in his reign. He introduced the law

code, with translations from the Ten Commandments,

Exodus 21-23

and the book of Acts 15:23-29.

For the majority of the people, the Bible was a book only

understood by the educated clergy.

Several factors caused a growing interest in the

Bible, one factor was the schism of the Catholic Church in

1378-1417, known as the Great Schism, causing there to be

two popes, one based in Rome and the other in Avignon,

challenging Papal authority, demonstrated Papal fallibility.

Another factor was the Black Death, the Bubonic

plague that caused the death of 30 to 40% of urban

populations. The plague resurfaced several times in 1360,

1369, 1374 causing the populations to be devastated. Life

expectancy in England dropped to seventeen years of age in

1376 from twenty-five in 1348. All this caused people to

look for answers, causing a revival in religious interest

among the laity. This growing interest in eternal matters

was hindered by the lack of resources.

One of the main issues was the role of the laity

and clergy. The Roman language, Latin, became the language

of the clergy. Most of the laity could not read or

understand Latin. The Bible, the Latin Vulgate, first

translated in the 4th century by Jerome from the Septuagint

and then later from the Hebrew was inaccessible to English

speaking people.

John Wycliffe

To

remedy the problem of accessibility, John Wycliffe (1320-84)

an oxford scholar, began to translate parts of the Bible

into English. Wycliffe also challenged Roman doctrines,

such as transubstantiation

and the role of the church in national politics. His

students would carry his views to the rest of England,

traveling preachers known as the Lollards (derived from

lowlanders, used in the sense of heretics) He completed the

translation of the New Testament in 1380. Four years after

his death the Old Testament translation was completed by

John Purvey (1354-1428), Wycliffe’s secretary. The basis

Wycliffe’s translation was the Latin Vulgate. Purvey’s

edition became the dominant English translation for almost

200-years.

To

remedy the problem of accessibility, John Wycliffe (1320-84)

an oxford scholar, began to translate parts of the Bible

into English. Wycliffe also challenged Roman doctrines,

such as transubstantiation

and the role of the church in national politics. His

students would carry his views to the rest of England,

traveling preachers known as the Lollards (derived from

lowlanders, used in the sense of heretics) He completed the

translation of the New Testament in 1380. Four years after

his death the Old Testament translation was completed by

John Purvey (1354-1428), Wycliffe’s secretary. The basis

Wycliffe’s translation was the Latin Vulgate. Purvey’s

edition became the dominant English translation for almost

200-years.

The Catholic Church was so opposed to Wycliffe

translating the Bible into the English language that in the

year 1415, the Council of Constance ordered his bones

exhumed and burned, and his ashes to be scattered in the

river Swift. People caught reading the Bible were liable to

loose their land, cattle , life and goods. In 1408, a synod

at Oxford decreed it as unlawful to read Wycliffe’s Bible,

declaring,

It is a dangerous thing….as witnesseth

blessed St. Jerome, to translate the text of the holy

Scripture out of one tongue into another; for in the

translation the same sense is not always easily kept, as the

same St. Jerome confesseth, that although he were

inspired...yet oftentimes in this he erred; we therefore

decree and ordain that no man hereafter by his own

authority… translate any text of the Scripture into English

or any other tongue, by way of a book, pamphlet, or

treatise; and that no man read any such book, pamphlet or

treatise, now lately composed in the time of John Wycliffe

or since or hereafter to be set forth in part or in whole,

publicly or privately, upon pain of greater excommunication,

until the said translation be approved by the ordinary of

the place or, if the case so require, by the council

provincial. He that shall do contrary to this shall

likewise be punished as a favourer of heresy and error.

Still people paid to borrow the Wycliffe bible, with the

price being recorded as a load of hay, to read the Bible an

hour a day over a period

.

In 1455, Johannes Gutenberg invented a printing

press using movable type. Gutenberg’s first work was the

printing of the Bible, the Latin Vulgate. Gutenberg’s

printing became known as the Forty-Two-line Bible,

because of 42-lines in a column. Gutenberg’s invention

solved a major problem for scripture transmission. With the

printing press, human error in text copying was virtually

eliminated. In addition, copies could be made much quicker

and less expensive than hand copies, making books and Bibles

available to the masses.

William

Tyndale (1494-1536) Tyndale Translation

William

Tyndale (1494-1536) Tyndale Translation

William Tyndale, a Catholic priest, (1492-1536)

born in Gloucestershire, went to Oxford at the age of

sixteen. After receiving his Master of Arts degree, he

taught at Oxford for a year and then at Cambridge. During

this period, he became aware of the lack of scripture

knowledge amongst the priests and laity. In a debate with an

English priest, Tyndale showed his early desire to make

scripture available to all,

Not long after, Tindall happened to be in the company of a

certain divine, recounted for a learned man, and in

disputing with him drave him to that issue, that the great

doctor burst out into these blasphemous words: “We are

better to be without God’s law than the Pope’s. Master

Tindall, replied, “I defy the Pope and all his laws,” and

added that if God spared him life, ere many years he would

cause a boy that driveth the plough to know more of

Scripture than he did.”

He took on the task of establishing an English translation

of the Bible based on the Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek text.

The first Hebrew Bible was published in 1488, along with the

Hebrew Lexicon in 1506. Tyndale planned to use these for an

English translation of the scripture. Martin Luther

published his German translation in 1522, but Tyndale needed

permission of the church to translate the Bible. The Church

of Rome opposed his plans his plans to translate the Bible

into English.

Tyndale left for Cologne in 1525, but the church

prevented the printer from completing the job, Tyndale

rescued 6000 copies of Matthew chapters 1-22 already printed

and fled to Worms, in Germany. In Worms, he completed two

editions and had them smuggled to England (1525). The

Bishop of London, Cuthbert Tunstall purchased as many copies

as possible and had them burned. Of the 18,000 copies

smuggled only two remain.

Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor considered

Tyndale a heretic and had him kidnapped in Antwerp, Belgium

and imprisoned. Later found guilty of heresy, Tyndale

removed from his priestly office, was handed over to secular

powers for execution in August 1536. Burning at the stake,

Tyndale cried, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes”.

This statement would seem prophetic as Tyndale’s version of

the New Testament provided the basis for all successive

versions between his day and ours. The King James Version

is practically a fifth revision of Tyndale’s revision.

The basis of Tyndale’s New Testament was the

Erasmus 2nd or 3rd edition of the

Greek New Testament printed in 1519 and 1522. Tyndale used

the Hebrew Bible and Lexicon to translate portions of the

Old Testament. Miles Coverdale would complete and edit

portions of the Old Testament, after Tyndale’s death. This

became known as the Coverdale translation (1535).

Another of Tyndale’s disciples John Rogers, was

the force behind the Matthew’s Bible (1537), Henry

the VIII allowed the Bible to be distributed throughout

England. This free flow of scriptures caused many

theologians concern. Edward Foxe, complained “The lay people

do now know the holy scripture better than many of us; and

the Germans have made the text of the Bible so plain and

easy by the Hebrew and Greek tongue that now many things may

be better understood without any glosses at all than by all

the commentaries of the doctors”

William Coverdale (1488-1569), The

Great Bible

The atmosphere changed in England as Rome and

Henry the VIII came into conflict. Henry the VII wanted to

divorce his Catholic wife, Katherine of Aragon, the Catholic

Church refused. When the Pope refused, Henry VII renounced

the Catholic Church and appointed himself head of the Church

of England. To spite the Catholic Church and unify his

kingdom, he ordered the Bible printed and translated into

English, and placed in all the churches, the translation

they placed in the churches was the Great Bible. Miles

Coverdale was the editor behind the Great Bible, which used

the Matthew’s Bible as its basis. The size of the Bible, 16

½ inches by 11 inches was the reason it was called the Great

Bible.

The Geneva Bible (1560)

When Mary Tudor (1553-1558) (Daughter of Henry

VIII) became Queen of England, she tried to restore

Catholicism Protestants were persecuted and killed. Many

fled to John Calvin’s Geneva, where another translation of

the English Bible was prepared, the Geneva Bible.

The Geneva Bible translation (1557, 1560) was done under

the direction of William Coverdale and John Knox and

influenced by John Calvin. This Bible became popular in

England after Mary Tudor’s execution and Protestant

persecution stopped. An act of the Scottish Parliament

required it compulsory for every householder who had an

income above a certain amount, to buy a copy of the Geneva

Bible. The popularity of the Geneva Bible with Protestants

caused the Great Bible’s revision. This revised edition

later became known as the Bishop’s Bible (1568).

The marginal notes of the Geneva Bible had a

Calvinist theology, which caused concern for the Church of

England. To counter this concern, Matthew Parker, Archbishop

of Canterbury, who recognized the superior quality of the

Geneva translation, published the Bishop’s Bible in 1568 to

counter its theology.

The Douay-Rheims Bible (New Testament

1582, Old Testament 1609-10)

With the popularity of the Geneva Bible and its

marginal notes, the Catholic Church was forced to respond

with their own English translation. William Allen an Oxford

fellow and strict Catholic, fled to Europe, when Elizabeth I

came to the throne. He established and English College in

Douay, France 1568. The college was later forced to move to

Rheims in 1578, where the New Testament was published. The

college returned to Douay, France in 1593 where the Old

Testament was published, hence the name Douay-Rheims.

The source text used in the translation was the

Latin Vulgate. The translators made their aims clear in the

preface, “To meet the Protestant challenge, priests must

be ready to quote Scripture in the vulgar tongue since their

adversaries have every favorable passage at their fingers’

ends; they must know the passages correctly used by

Catholics in support of our faith, or impiously misused by

heretics in opposition to the Church’s faith”

The apocryphal books are interspersed among the

canon as in the Latin Vulgate.

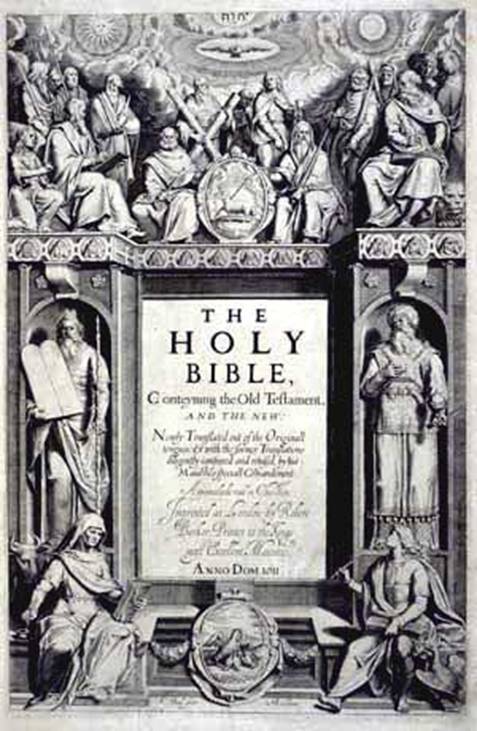

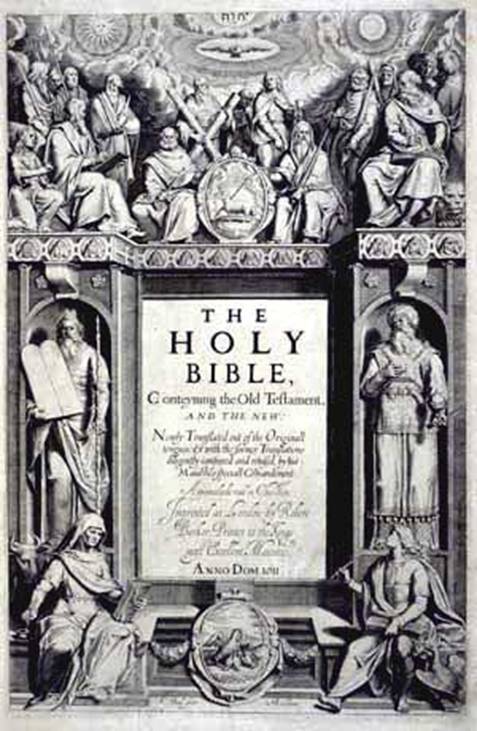

The King James Bible ( KJV 1611)

In 1604, the Puritan Party made a petition to

King James I (1603-1625) called the Millenary Petition,

about grievances between the Puritans and the English

Church. John Reynolds, the Puritan president of Corpus

Christi College, Oxford raised the question of having an

authorized version of the English Bible that would be

acceptable to all parties. This Bible was to replace both

the Bishop’s Bible and the Geneva Bible as the

English translation. The purpose of this new translation was

to have a Bible, that could be read in church services and

at home.

Six companies of men totaling 54 were assigned

with only 47 actually working on the revision of the Bible.

Each committee had a set of instructions. All other English

translations were to be consulted as well as the Hebrew and

Greek Texts but the Bishops Bible was to be used as the base

in translation. Their finished work is known as the King

James Authorized Bible.

The Hebrew Text used was second edition of the

Rabbinic Bible prepared by Jacob ben Chayim published

by Bromberg (1524-1525). The New Testament consulted the

work commonly known as Textus Receptus or the

“Received Text”. Beza’s Greek New Testament of 1565 was the

underlying text of the New Testament used in the King James

Bible, which became known as Textus Receptus. The King

James 1611 translation also became known

by the name Textus Receptus or received text.

King James established the principles for the

translation of the Authorized Version, hence the name

authorized.

1. The 1602 version of the Bishop’s Bible was to be used as

the basis of the translation, but the original Greek and

Hebrew were to be examined. Other translations were also to

be consulted to determine the best reading of the Hebrew and

Greek.

2. So the translation did not become too stilted a variety

of words were to be used for the same Greek and Hebrew

words.

3. Words necessary in English but not in Hebrew or Greek

were to be set in Italics.

4. Names of biblical characters were to correspond as

closely as possible to those in common use; however names

were not standardized. Example Jesus and Joshua.

5. Old Ecclesiastical words were to be maintained,

congregation and washing in the Tyndale’s translation became

“Church” and “Baptism” in the Authorized Version.

6. No marginal notes were to appear other then to explain

the Hebrew and Greek words.

7. Existing chapter and verse divisions were to be retained,

but new headings would be supplied.

The

translation of the Bible from its original languages

(Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek), is a complex story. The

process of translation for each language is story in

itself. As the Gospel spread to other lands, the books of

the Bible, both Old and New Testaments were also translated,

some earlier then others.

The

translation of the Bible from its original languages

(Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek), is a complex story. The

process of translation for each language is story in

itself. As the Gospel spread to other lands, the books of

the Bible, both Old and New Testaments were also translated,

some earlier then others.

The church in England was well enough established by the

4th century to send three British bishops—of Londinium

(London), Eboracum (York), and Colonia Linum (Lincoln)—to

the Council of Arles (in modern France) in 314. However,

there is no record of the Bible’s translation into the

English language at this point. Latin was the language of

Rome and its various outposts, including England.

The church in England was well enough established by the

4th century to send three British bishops—of Londinium

(London), Eboracum (York), and Colonia Linum (Lincoln)—to

the Council of Arles (in modern France) in 314. However,

there is no record of the Bible’s translation into the

English language at this point. Latin was the language of

Rome and its various outposts, including England.  To

remedy the problem of accessibility, John Wycliffe (1320-84)

an oxford scholar, began to translate parts of the Bible

into English. Wycliffe also challenged Roman doctrines,

such as transubstantiation

To

remedy the problem of accessibility, John Wycliffe (1320-84)

an oxford scholar, began to translate parts of the Bible

into English. Wycliffe also challenged Roman doctrines,

such as transubstantiation William

Tyndale (1494-1536) Tyndale Translation

William

Tyndale (1494-1536) Tyndale Translation