|

Chapter Five

The Compilation of the Text of the

Quran

1. The Initial

Collection of the Quran

The First Collection

Under Abu Bakr

Most books are written

out as a complete text from cover to cover with the

outline from the introduction to the conclusion planned

well in advance before a word is written. The quran

Qurčan, on the other hand, was never compiled into book

form during the time of Muhammad and it was only his

death which actually completed its text. It came to him

during his lifetime in staggered portions and although

its final form had been settled in principle prior to

his death there was no single collection of its surahs

and passages in a written form in anyone's possession.

While he lived there was

always a possibility that fresh revelations could be

added to the text. Indeed it would have seemed

inappropriate to any of his companions to attempt to

codify it in written form, especially as the main means

of retaining its contents at the time was in the memory

of those who had consciously endeavoured to learn the

quran Qurčan by heart. Some of it had been written out

on different materials such as pieces of wood,

palm-leaves and the like. It also appears that new

passages were coming to Muhammad with increasing

frequency shortly before his demise, making an attempt

at a single collection even more improbable:

Allah sent down his

Divine Inspiration to His Apostle (saw) continuously and

abundantly during the period preceding his death till He

took him unto Him. That was the period of the greatest

part of revelation, and Allah's Apostle (saw) died after

that. (Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6, p.474).

It is expressly stated by

one of the major Muslim scholars of the quran Qurčan in

Islamic history that the text had been completely

written down and carefully preserved but that it had not

been assembled into a single location during the

lifetime of the Prophet (As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii `Ulum

quran al-Qurčan, p.96). Once the primary recipient of

the quran Qurčan had passed away, however, it was only

logical that a collection should be made of the whole

quran Qurčan into a single text. The traditions of Islam

state that four men knew the quran Qurčan during

Muhammad's lifetime in its entirety, one of whom was

Zaid ibn Thabit (Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.5, p.97). He was

soon called upon to compile a written codex of the text.

Shortly after the

Prophet's death a number of tribes recently converted to

Islam in the Arabian Peninsula reverted to Arabian

paganism and revolted against Muslim rule. Muhammad's

successor Abu Bakr sent an army to subdue them and in

the subsequent Battle of Yamama a number of the

companions who knew the quran Qurčan directly from their

Prophet were killed. Others with a similar knowledge

also passed away and with them their own readings of the

text:

Many of the companions of

the Prophet of Allah (saw) had their own readings of the

quran Qurčan, but they died and their readings

disappeared soon afterwards.

(Ibn Abi Dawud, Kitab

al-Masahif, p.83)

Abu Bakr realised that

there was a danger that the quran Qurčan might be lost

if any more of its best-known reciters passed away. He

told Zaid that he was a young man above suspicion who

had been known to write down portions of the quran

Qurčan and he accordingly commissioned him to search for

its portions and collect it into a single codex. Zaid

was initially taken back at the idea and later recorded

what followed:

By Allah! If they had

ordered me to shift one of the mountains, it would not

have been heavier for me than this ordering me to

collect the quran Qurčan. Then I said to Abu Bakr, "How

will you do something which Allah's Apostle (saw) did

not do?" Abu Bakr replied "By Allah, it is a good

project". (Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6, p.477).

Zaid eventually approved

after Abu Bakr and `Umar had pressed the urgency of the

task upon him and set about collecting the quran Qurčan.

It was to be a unique undertaking as the contents of the

book were spread widely among the companions and were

recorded on various materials. His hesitancy at first

shows that the project would not be easy. He did not

believe that either he or any of the other companions

who knew the text well could be relied on simply to

write it out from memory. Instead he proceeded to make a

thorough search for the text from a variety of sources

and he recorded his investigation in these words:

So I started looking for

the quran Qurčan and collected it from (what was written

on) palm-leaf stalks, thin white stones, and also from

men who knew it by heart, till I found the last verse of

Surat at-Tauba (repentance) with Abi Khuzaima al-Ansari,

and I did not find it with anybody other than him.

(Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6,

p.478).

The two primary sources,

amongst the others mentioned, were later defined as ar

riqaa ar-riqa a ("the parchments") and sudur ar-rijjal

("the breasts of men"), namely not only texts from those

who had memorised the quran Qurčan but also whatever

written materials he could find (As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan,

p.137). Nonetheless he was not the only companion of the

Prophet to begin to codify the quran Qurčan into a

single written text (a mushaf) and may not even have

been the first to succeed in doing so. The following

tradition states that another of the early reciters was

the first to write it down and collect it:

It is reported .. from

Ibn Buraidah who said: "The first of those to collect

the quran Qurčan into a mushaf (codex) was Salim, the

freed slave of Abu Hudhaifah".

(As Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii

`Ulum quran al-Qurčan, p.135).

This Salim is one of only

four men who was recommended by Muhammad as the best

reciters of the quran Qurčan from whom its contents

should be learnt (Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.5, p.96) and he

was one of the qurra ("reciters") killed at the Battle

of Yamama. As it was only after this battle that Zaid

began to collect his material Salim's codex must indeed

have preceded his as the first written copy of the quran

Qurčan. Nonetheless Islamic tradition pays primary

attention to Zaid's codex not only because it was called

for by the first Caliph himself but also for other

reasons which will shortly become apparent.

quran

Perspectives on Zaid's

Collection of the Qurčan

Muslims claim that the

quran Qurčan as it stands today is an exact record of

the original without so much as a dot or stroke ever

having been lost, changed, or substituted in any way.

This is a strange claim to make for a book which had to

be compiled piecemeal from various sources scattered

among the companions of Muhammad, particularly in the

light of further evidences that some passages have been

lost, that others have been abrogated, and that other

codices compiled about the same time as Zaid's had

numerous readings that differed from his and from each

other's. These evidences will shortly be considered. At

this point, however, it must be said that Zaid's final

compilation was the result of an honest human attempt to

collect the quran Qurčan as far as he was able to and

there is no reason to suspect that it does not generally

project the text as it stood by the time of the

Prophet's death.

There are evidences even

at this early stage, however, that portions of the quran

Qurčan were irretrievably lost at the Battle of Yamama

when many of the qurra who had memorised whole portions

of it had perished:

Many (of the passages) of

the quran Qurčan that were sent down were known by those

who died on the Day of Yamama ... but they were not

known (by those who) survived them, nor were they

written down, nor had Abu Bakr, `Umar or `Uthman (by

that time) collected the quran Qurčan, nor were they

found with even one (person) after them. (Ibn Abi Dawud,

Kitab al-Masahif, p.23).

The negative impact of

this passage can hardly be missed: lam yaalam

ya alam-"not known", lam yuktab"not written down", lam

yuwjad-"not found", a threefold emphasis on the fact

that these portions of the quran Qurčan which had gone

down with the qurra who had died at Yamama were lost

forever and could not be recovered.

There are evidences in

the tradition literature to show that even Muhammad

himself was occasionally inclined to forget portions of

the quran Qurčan. One of these taken from a major Hadith

work reads as follows:

Aishah said: A man got up

(for prayer) at night, he read the quran Qurčan and

raised his voice in reading. When morning came, the

Apostle of Allah (saw) said: May Allah have mercy on

so-and-so! Last night he reminded me of a number of

verses I was about to forget. (Sunan Abu Dawud, Vol.3,

p.1114).

There is no evidence to

suggest that Zaid had compiled an official or standard

codex of the quran Qurčan even though Abu Bakr was the

immediate successor of Muhammad as head of the Muslim

community. The object was apparently to ensure that he

was in possession of a complete written text to ensure

its preservation. For the next twenty years virtually

nothing is said of this codex other than that, by the

time of `Uthman's caliphate, it was in the private

possession of Hafsah, `Umar's daughter and one of

Muhammad's wives, and was kept under her bed.

It is important in

concluding a study of Zaid's text to analyse the comment

he made about two verses of the quran Qurčan which he

had searched for and had found only with Abu Khuzaimah.

The full text of his eventual discovery is recorded in

these words:

I found the last verse of

Surat at-Tauba (Repentance) with Abi Khuzaima al-Ansari,

and I did not find it with anybody other than him. The

verse is: "Verily there has come to you an Apostle from

amongst yourselves. It grieves him that you should

receive any injury or difficulty ... (till the end of

baraa Bara a)". (Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6, p.478).

It is quite clear from

this passage that Zaid was dependent on one source alone

for the last two verses of Surat at-Tauba. In fact there

is another tradition which shows that it was not Zaid

who sought earnestly for the exact text of a pair of

verses which he recalled but could not trace. In this

record it is stated that it was Abu Khuzaimah himself

who drew the attention of the compilers to a text they

were overlooking:

Khuzaima ibn Thabit said:

"I see you have overlooked (two) verses and have not

written them". They said "And which are they?" He

replied "I had it directly from the messenger of Allah

(saw) (Surah 9, ayah 128): `There has come to you a

messenger from yourselves. It grieves him that you

should perish, for he is very concerned about you: to

the believers he is kind and merciful', to the end of

the surah". `Uthman said "I bear witness that these

verses are from Allah".

(Ibn Abi Dawud, Kitab al-Masahif,

p.11).

The significant feature

of this passage is the implication that Zaid and his

redactors would have missed these verses completely had

Abu Khuzaimah not mentioned them. He makes a point of

the fact that he received them "directly" (tilqiyya)

from the Prophet meaning obviously that he had heard

them firsthand and had not obtained them from secondary

sources. The passage goes on to say that Abu Khuzaimah

was subsequently asked where they should be inserted in

the quran Qurčan and he suggested they be added to the

last part of the text to be revealed, namely the close

of Surat at-Tauba (baraa Bara a in the text).

For many years there was

no further development in reducing the text of the quran

Qurčan to a standard form for the whole Muslim

community. Events in the time of `Uthman's caliphate,

however, led to the next stage.

2. `Uthman's Recension

of Zaid's Compilation

The Order to Destroy

All the Other Codices

The codex of Zaid ibn

Thabit was clearly one of great importance and its

retention in official custody during the caliphates

respectively of Abu Bakr and `Umar testify to its key

significance during the time of the quran Qurčan's

initial codification. There can be little doubt,

however, that this codex was at no time publicised

during this period or declared to be the official text

for the whole Muslim world.

There were a number of

other masters among the qurra who had gone to great

lengths to memorise the quran Qurčan. Islamic tradition

states that by the time `Uthman became caliph twelve

years after the death of the Prophet there were written

codices in use in different provinces compiled by other

well-known companions, in particular `Abdullah ibn masud

Mas ud and Ubayy ibn kab Ka b. There was no official

reaction at first to this development as Zaid's text had

never been intended as an official copy and the

credibility of these men in their knowledge of the quran

Qurčan had never been doubted. They are mentioned along

with two others as having been acknowledged by Muhammad

himself during his lifetime as the foremost authorities

on the quran Qurčan:

Narrated Masruq:

`Abdullah bin masud Mas ud was mentioned before

`Abdullah bin `Amr who said "That is a man I still love,

as I heard the Prophet (saw) saying, `Learn the

recitation of the quran Qurčan from four: from `Abdullah

bin masud Mas ud - he started with him - Salim, the

freed slave of Abu Hudhaifa, muadh Mu adh bin Jabal and

Ubai bin kab Ka b'". (Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.5, p.96).

The special mention of

the fact that Muhammad started with `Abdullah ibn masud

Mas ud indicates that the Prophet regarded him as the

most knowledgeable quran Qurčan reciter among his

companions. In fact, while the codices of this man and

other prominent reciters became prominent in the

developing Muslim world the codex of Zaid faded into

virtual obscurity. It had simply receded into the

private custody of Hafsah, one of the widows of the

Prophet (Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6, p.478).

Seven years after his

accession to leadership of the Muslim world, however,

`Uthman was faced with a crisis which threatened to

break up the Muslim world and undermine his unchallenged

leadership over it. It came from the very areas where

the other companions were so highly respected because of

their unique knowledge of the quran Qurčan and the fame

their codices enjoyed. Circumstances gave him an

opportunity to severely subvert their authority by

ordering that their codices be destroyed in the

interests of standardising one text for the whole Muslim

community. His opportunity came when the Muslim general

Hudhayfah ibn al-Yaman, leading an expedition of Muslim

forces from what is today Syria and Iraq, discovered

that the people there were disputing with each about the

reading of the quran Qurčan. The codex of `Abdullah ibn

masud Mas ud was the standard text of the Muslims at

Kufa while that of Ubayy ibn kab Ka b held sway in

Damascus. Hudhayfah immediately reported the matter to

`Uthman. What followed is described in the following

tradition:

Hudhaifa was afraid of

their (the people of sham Sha m and Iraq) differences in

the recitation of the quran Qurčan, so he said to

`Uthman, `O Chief of the Believers! Save this nation

before they differ about the Book (quran Qurčan) as Jews

and Chrstians did before'. So `Uthman sent a message to

Hafsa, saying, `Send us the manuscripts of the quran

Qurčan so that we may compile the quranic Qurčanic

materials in perfect copies and return the manuscripts

to you'. Hafsa sent it to `Uthman. `Uthman then ordered

Zaid ibn Thabit, `Abdullah bin az-Zubair, said Sa id bin

as al- As, and `Abdur-Rahman bin Harith bin Hisham to

rewrite the manuscripts in perfect copies. `Uthman said

to the three Quraishi men, `In case you disagree with

Zaid bin Thabit on any point in the quran Qurčan, then

write it in the dialect of the Quraish as the quran

Qurčan was revealed in their tongue'. They did so, and

when they had written many copies, `Uthman returned the

original manuscripts to Hafsa. `Uthman sent to every

Muslim province one copy of what they had copied, and

ordered that all the other quranic Qurčanic materials,

whether written in fragmentary manuscripts or whole

copies, be burnt.

(Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6,

p.479).

There is no suggestion

that he considered the other codices to be unreliable.

It was the divisions between the Muslims in the reciting

of the text that made him realise the need to act as he

foresaw the possibility that the Muslim world would

break up into sects and divisions. By unifying the

people on a single text of the quran Qurčan he saw an

occasion to prevent such a partition occurring. The

following tradition gives a balanced picture of the

circumstances and explains why he chose Zaid's codex as

the basis on which the quran Qurčan text was to be

standardised for the Muslim community. `Ali is reported

to have said of `Uthman:

By Allah, he did not act

or do anything in respect of the manuscripts (masahif)

except in full consultation with us, for he said, "What

is your opinion in this matter of qiraat qira at

(reading)? It has been reported to me that some are

saying `My reading is superior to your reading'. That is

a perversion of the truth". We asked him, "What is your

view (on this)?" He answered, "My view is that we should

unite the people on a single text (mushaf wahid), then

there will be no further division or disagreement". We

replied "What a wonderful idea!" Someone from the

gathering there asked, "Whose is the purest (Arabic)

among the people and whose reading (is the best)?" They

said the purest (Arabic) among the people was that of

said Sa id ibn as al- As and the (best) reader among

them was Zaid ibn Thabit. He (`Uthman) said, "Let the

one write and the other dictate". Thereafter they

performed their task and he united the people on a

(single) text.

(Ibn Abi Dawud, Kitab

al-Masahif, p.22).

The motive is twice

stated in this extract to simply be the desire to bring

consensus among the Muslims on the basis of a single

text. If any of the leaders involved in the process had

believed that the other codices were unreliable or that

Zaid's was a perfect compilation of the quran Qurčan to

the last dot and letter they would simply have ordered

their scribes to transcribe it. Their decision to choose

Zaid and said Sa id because of their proficiency in the

reading and Arabic knowledge of the quran Qurčan

respectively shows that, as at the time when Zaid's text

was first commissioned, the aim was to get as close to

the original as possible.

The question that might

well be asked, however, is why Zaid's text was called

for and why copies were made to be sent as the official

copies of the quran Qurčan in each province while the

others then in use had to be burnt and destroyed. One

reason has already been given, namely to reimpose `Uthman's

authority over the Muslims scattered throughout the

Muslim provinces. Zaid's text, being kept in official

custody at Medina, was ideal for this purpose. Also, it

had not been in general public use so there had been no

division about its contents. The standardising of a

Medinan text at the seat of the Caliph's government

enabled him to suppress the popularity of other reciters

in areas where he was becoming unpopular. He was placing

members of his own family, the descendants of Umayya who

had opposed Muhammad until the conquest of Mecca, in

positions of authority over them. Zaid's text was thus

chosen not because it was believed to be superior to the

others but because it suited `Uthman's purposes in

standardising the text of the quran Qurčan.

The fact that none of the

other texts was spared shows that not one of them,

Zaid's included, was in complete agreement with any of

the others. There must have been serious textual

variants between the codices to warrant such drastic

action. The order to consign all but one of the written

texts (masahif) to the flames indicates that serious

divisions existed between them. This was perhaps a

circumstance to be expected when it is remembered that

the quran Qurčan had not been reduced to a single text

at Muhammad's death. At the time it was widely scattered

piecemeal among a number of his companions and that

mainly in their memories, the most fallible of sources.

quran

The Revision of Zaid's

Codex of the Qurčan

Muslims often claim that

all that `Uthman sought to achieve was to cancel out the

different readings of the quran Qurčan in its various

dialects. The issue was, they say, purely one of

eliminating different pronunciations. This line of

reasoning is subjectively advanced to maintain the

hypothesis that the quran Qurčan, in its written form,

is a divinely preserved and therefore perfect text.

There were no vowel points, however, in those early

codices and any differences in pronunciation would not

have appeared in the texts. He could only have ordered

the burning of all other codices if there were serious

differences in the text itself. Evidences will be given

in the next section to show that this was indeed the

case.

In fact, shortly after

his decree had been put into effect, `Uthman enquired

what the grievances were of the Muslims whose opposition

to him was intensifying. One of their complaints was

that he had "obliterated the Book of Allah" (Ibn Abi

Dawud, Kitab al-Masahif, p.36). They did not accuse him

simply of destroying their masahif (codices) but of

burning the kitabullah, the quran Qurčan, itself.

Although his action contributed towards the

standardising of an official text it also left a keen

antagonism as they believed he had ruined authentic

manuscripts of the quran Qurčan compiled by some of

Muhammad's closest companions.

There are further

evidences that Zaid's codex was not at this time

considered an infallible copy of the quran Qurčan.

`Uthman not only ordered his text to be copied but also

called for it to be revised at the same time. When he

appointed the four redactors mentioned he chose the

other three because they were from the Quraish tribe at

Mecca while Zaid came from among the ansar of Medina. He

said that, if they should differ at any point in respect

of the language of the quran Qurčan, they were to

overrule Zaid and write it in the Quraish dialect as it

had been originally revealed in it (Sahih al-Bukhari,

Vol.4, p.466).

At the same time Zaid,

after the manuscripts had been copied out, suddenly

remembered another text that was missing from the quran

Qurčan:

Zaid said "I missed a

verse from al-Ahzab (Surah 33) when we transcribed the

mushaf. I used to hear the messenger of Allah (saw)

reciting it. We searched for it and found it with

Khuzaimah ibn Thabit al-Ansari: `From among the

believers are men who are faithful in their covenant

with Allah' (33.23). So we inserted it in the (relevant)

surah in the text".

(As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii

`Ulum quran al-Qurčan, p.138).

A similar record of this

omission is recorded in Sahih al-Bukhari (Vol.6, p.479).

It shows that even Zaid's original attempt to produce a

complete codex was not entirely successful. It is

remarkable in the light of these evidences to hear

Muslims not only claiming that the quran Qurčan in their

hands today is an exact, perfect redaction of the

original but also alleging that this proves the divine

origin of the book. The facts show otherwise. It was not

Allah who arranged the text in its present form but

rather the young man Zaid and that only according to the

best of his ability. Nor was it Muhammad who codified or

standardised it for the Muslim ummah but `Uthman and

that only after a complete revision of one codex at the

expense of all the others. The quran Qurčan in the

possession of Muslims today is simply a revised edition

of Zaid's initial compilation.

Even after this time

disputes still arose regarding the authenticity of the

text. A good example concerns a variant reading of Surah

2.238 which, in the quran Qurčan standardised by

`Uthman, reads "Maintain your prayers, particularly the

middle prayer (as-salaatil wustaa), and stand before

Allah in devoutness". The variant reading is given in

this hadith:

`Aishah ordered me to

transcribe the Holy quran Qurčan and asked me to let her

know when I should arrive at the verse Hafidhuu

alaas-salaati waas-salaatil wustaa wa quumuu lillaahi

qaanitiin (2.238). When I arrived at the verse I

informed her and she ordered: Write it in this way,

Hafidhuu alaas-salaati waas-salaatil wustaa wa salaatil

asri salaatil- asri wa quumuu lillaahi qaanitiin. She

added that she had heard it so from the Apostle of Allah

(saw). (Muwatta Imam Malik, p.64).

`Aishah was a very

prominent woman in Islam being one of the widows of the

Prophet, and she would not have recommended such a

change lightly. She ordered the scribe to add the words

wa salaatil `asr meaning "and the afternoon prayer",

giving Muhammad himself as the direct source of her

authority for this reading. On the same page there is a

similar tradition where Hafsah, another of his widows,

ordered her scribe `Amr ibn Rafi to make the same

amendment to her codex. It is known that Hafsah had a

codex of her own in addition to the codex of Zaid in her

possession. Ibn Abi Dawud refers to it as a separate

manuscript under the heading Mushaf Hafsah Zauj an-Nabi

(saw) ("The Codex of Hafsah, the Widow of the Prophet").

He specifically records this same incident as a variant

reading in her codex:

It is written in the

codex of Hafsah, the widow of the Prophet (saw):

"Observe your prayers, especially the middle prayer and

the afternoon prayer". (Ibn Abi Dawud, Kitab al-Masahif,

p.87).

Ibn Abi Dawud also states

on the same page that this variant was found in the

codices of Ubayy ibn kab Ka b, Umm Salama and Ibn Abbas.

Some commentators accepted that it contained an

injunction to specially observe the afternoon prayer in

addition to the midday prayer while others said it was

merely an elaboration of the text and that the

salatil-wusta was the same as the salatil asr

salatil- asr as in this tradition:

It is said by Abu Ubaid

in his Fadhail quran al-Qurčan ("The Excellences of the

quran Qurčan") that the purpose of a variant reading (qiraatash

shaathat al-qira atash-shaathat) is to explain the

standard reading (qiraatal mashhuurat al-qira atal-mash huurat)

and to illustrate its meaning, as in the (variant)

reading of `Aishah and Hafsah, wa salaatil wustaa

salaatil 'asr.

(As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii

`Ulum quran al-Qurčan, p.193).

It was variants such as

this that led to Hafsah's codex being destroyed when

Marwan ibn al-Hakam was governor of Medina some time

after the death of `Uthman. While Hafsah was still alive

she refused to give it up though he anxiously sought to

destroy it (Ibn Abi Dawud, Kitab al-Masahif, p.24) and

it was only upon her death that he got hold of it and

ordered its destruction fearing, he said, that if it

became well-known the same variant readings `Uthman

sought to suppress would occur again.

The Muslim world today

boldly professes a single text of the quran Qurčan yet

those of `Uthman's time accused him, saying that the

quran Qurčan had been in many books and that he had

discredited them all except one. A high price had been

paid to obtain one standardised text for all time.

3. Variant Readings in

the Other Codices

masud quran

`Abdullah Ibn Mas ud: An

Authority on the Qurčan

Although `Uthman

succeeded in destroying the other codices he was unable

to suppress the fact that they had been compiled.

Because the preferred method of learning the quran

Qurčan was still by memorisation he could not entirely

eliminate the variant readings known to exist between

them and Zaid's codex. He also had to contend with the

fact that many of their compilers were renowned quran

Qurčan reciters. One of the best known was `Abdullah ibn

masud Mas ud who is recorded as being "the first man to

speak the quran Qurčan loudly in Mecca after the

apostle" (Ibn Ishaq, Sirat Rasulullah, p.141). The

hadith record which records that Muhammad specifically

started with him as a leading authority on the quran

Qurčan is supported by the following tradition where he

expresses his own knowledge of the book:

There is no Sura revealed

in Allah's book but I know at what place it was

revealed; and there is no verse revealed in Allah's Book

but I know about whom it was revealed. And if I know

that there is somebody who knows Allah's Book better

than I, and he is at a place that camels can reach, I

would go to him.

(Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6,

p.488).

In a similar tradition he

added to this that he had once recited more than seventy

surahs in Muhammad's presence and claimed that all of

the Prophet's companions were aware that no one knew the

quran Qurčan better than he. Shaqiq, one of the

companions sitting there, stated that no one argued with

him or found any fault in his recitation (Sahih Muslim,

Vol.4, p.1312). It also cannot be doubted that he was

one of those who collected the quran Qurčan into written

form shortly after Muhammad's death. Ibn Abi Dawud

devotes no less than nineteen pages to the variant

readings between his text and that of Zaid ibn Thabit

(Kitab al-Masahif, pp. 54-73). It is also well known

that Ibn masud Mas ud initially refused to hand his

codex over for destruction and for a while after one of

the copies of Zaid's manuscript arrived at Kufa the

majority of the Muslims there still adhered to Ibn masud

Mas ud's text.

There are solid evidences

that his reason for resisting `Uthman's order was that

he considered his own codex to be far superior to Zaid's

and before Hudhayfah ever reported the existence of

variant readings to the Caliph he had some sharp words

with him.

Hudhaifah said "It is

said by the people of Kufa `the reading of `Abdullah

(ibn masud Mas ud)', and it is said by the people of

Basra `the reading of Abu Musa'. By Allah! If I come to

the Commander of the Faithful (`Uthman), I will demand

that they be drowned". `Abdullah said to him "Do so, and

by Allah you also will be drowned, but not in water".

(Ibn Abi Dawud, Kitab

al-Masahif, p.13).

When Hudhayfah also

challenged him that he had been sent to the people of

Kufa as their teacher and there had made them submit to

his reading of the quran Qurčan, Ibn masud Mas ud

replied that he had not led the people astray, again

claiming that no one knew the quran Qurčan better that

himself (Ibn Abi Dawud, p.14). On another occasion he

had this to say about his knowledge of the quran Qurčan

in contrast with Zaid's proficiency:

I acquired directly from

the messenger of Allah (saw) seventy surahs when Zaid

was still a childish youth - must I now forsake what I

acquired directly from the messenger of Allah?

(Ibn Abi Dawud, Kitab

al-Masahif, p.15).

It is also recorded that

when news of `Uthman's order to destroy the other

codices and to use Zaid's alone to obtain uniformity in

reading reached Kufa Ibn masud Mas ud gave a khutba, a

sermon on the subject and declared to the Muslims of the

city:

The people have been

guilty of deceit in the reading of the quran Qurčan. I

like it better to read according to the recitation of

him (Prophet) whom I love more than that of Zayd Ibn

Thabit. By Him besides whom there is no god! I learnt

more than seventy surahs from the lips of the Apostle of

Allah, may Allah bless him, while Zayd ibn Thabit was a

youth, having two locks and playing with the youth.

(Ibn sad Sa d, Kitab

al-Tabaqat al-Kabir, Vol.2, p.444).

One thing is obvious from

these statements - Ibn masud Mas ud regarded his codex

as a more authentic record of the original quran Qurčan

text than the one compiled by Zaid and standardised by

`Uthman as the sole text to be used throughout the

Muslim world thereafter.

Muslim writers try to get

around the implications of these evidences by suggesting

that it was only a sentimental attachment to his codex

that made Ibn masud Mas ud react so strongly against the

Caliph's order or, once again, that the variant readings

were confined solely to differences in pronunciation. It

is quite clear, however, that it was his conviction that

his codex was superior to Zaid's that made him angry

and, as shall be seen, the variant readings related to

real differences in the text itself.

The Variant Readings in

the Other Codices

One of the interesting

facets of Ibn masud Mas ud's codex was the total

omission of the opening chapter, the Suratul-Fatihah,

from his text as well as the muawwithatayni

mu awwithatayni, the last two surahs of the quran

Qurčan. The form of these chapters has some

significance-the first is purely a prayer to Allah and

the last two are "charm" surahs against evil forces. In

all three the words are the expression of the believer

as speaker rather than Allah himself. The possibility

that Ibn masud Mas ud had denied the validity of these

surahs troubled early Muslim historians. Fakhruddin

ar-Razi, the author of a commentary on the quran Qurčan

titled Mafatih al-Ghayb ("The Keys of the Unseen") who

lived in the sixth century of Islam admitted that this

had "embarrassing implications" and used the strange

reasoning that Ibn masud Mas ud had probably not heard

himself from the Prophet that they were to be included

in the quran Qurčan. Ibn Hazm, another scholar, simply

charged without giving any reasons that this was "a lie

attributed to Ibn masud Mas ud". Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani,

however, in his famous Fath al-Baari (a review of the

Sahih al-Bukhari) accepted these reports as sound,

stating that Ibn masud Mas ud had omitted them because

the Prophet, to his knowledge, had only commanded that

the surahs be used as incantations against evil forces

and that, while he accepted them as sound, he had been

reluctant to include them in his text (As-Suyuti,

Al-Itqan, pp.186-187).

There were numerous

differences between Ibn masud Mas ud's codex and Zaid's

in respect of the rest of the text and no less than

one-hundred-and-one occur in Suratul-Baqarah alone. A

review of some these will indicate the nature of these

variant readings.

Surah 2.275 begins with

the words Allathiina yaakuluunar-ribaa laa yaquumuuna -

"those who devour usury will not stand". Ibn masud

Mas ud's text had the same introduction but added the

words yawmal qiyaamati, namely "on the Day of

Resurrection". The variant is mentioned in Abu Ubaid's

Kitab Fadhail quran al-Qurčan and was also recorded in

the codex of Talha ibn Musarrif, a secondary codex said

to have been dependent on Ibn masud Mas ud's text, Talha

likewise being based at Kufa.

Surah 5.91, in the

standard text, contains the exhortation fasiyaamu

thalaathati ayyaamin-"fast for three days". Ibn masud

Mas ud's text added the adjective mutataabiaatin

mutataabi aatin meaning three "successive" days. This

variant is derived from at-Tabari's famous commentary

titled jami Jami al-Bayan `an tawil Ta wil ay quran

al-Qurčan (7.19.11) and was also mentioned by Abu Ubaid.

This variant wasfound in Ubayy ibn kab Ka b's text as

well as in the codices of Ibn `Abbas and Ibn masud

Mas ud's pupil Ar-Rabi ibn Khuthaim.

Surah 6.153 begins Wa

anna haathaa siraati-"Verily this is my path". Ibn masud

Mas ud's text read Wa haathaa siraatu rabbakum-"This is

the path of your Lord". The variant derives again from

at-Tabari (8.60.16). Ubayy ibn kab Ka b had the same

reading, except that for rabbakum his text read rabbika.

The secondary codex of amash Al-A mash, mentioned by Ibn

Abi Dawud in his Kitab al-Masahif (p.91), also began

with the variant wa haathaa as in the texts of Ibn masud

Mas ud and Ubayy ibn kab Ka b. Ibn Abi Dawud also adds a

further variant, suggesting that Ibn masud Mas ud read

the word siraat with the Arabic letter sin rather than

the standard sad (Kitab al-Masahif, p.61).

Surah 33.6 contains the

following statement about the relationship between

Muhammad's wives and the community of Muslim believers:

wa azwaajuhuu ummahaatuhuu-"and his wives are their

mothers". Ibn masud Mas ud's text added the words wa

huwa abuu laahum-"and he is their father". This variant

is also recorded by at-Tabari (21.70.8) and was also

recorded in the codices of Ubayy ibn kab Ka b, Ibn

`Abbas, Ikrima and Mujahid ibn Jabr except that in the

last three texts mentioned the statement that Muhammad

is their father precedes the one which makes his wives

their mothers. The codex of Ar-Rabi ibn Khuthaim,

however, follows Ibn masud Mas ud's in placing it at the

end of the clause. The considerable number of references

for this variant reading argue strongly for its possible

authenticity over and against its omission in the codex

of Zaid ibn Thabit.

In many other examples

the variant relates to the form of a word which has

slightly altered its meaning, as in Surah 3.127 where

Ibn masud Mas ud and Ubayy ibn kab Ka b both read wa

saabiquu ("be ahead") for wa saariuu saari uu ("be

quick") in the standard text. The variant again derives

from at-Tabari (4.109.15). In other instances a single

word has been added not affecting the sense of the text

as in Surah 6.16 where once again Ibn masud Mas ud and

Ubayy ibn kab Ka b recorded the same variant, namely

yusrifillaahu-"averted by Allah" - for the standard

yusraf-"averted". This variant is recorded in Maki's

Kitab al-Kasf.

It is important to

remember that these are not variants which reflect

adversely on the codices which were destroyed as though

the text standardised by `Uthman was above reproach

while all these were full of aberrant readings. Zaid's

codex was just one of many which had been compiled

shortly after Muhammad's death and it was purely as a

matter of convenience that it was preferred above the

others. The prominence which Ibn masud Mas ud enjoyed as

a reciter, and his claim that he knew the quran Qurčan

better than Zaid, should also be remembered. It is also

most significant to find that Ubayy ibn kab Ka b also

was regarded as one of the best readers of the quran

Qurčan by the Prophet himself:

Affan ibn Muslim informed

us .. on the authority of Anas ibn Malik, he on the

authority of the Prophet, may Allah bless him; he said:

The best reader (of the quran Qurčan) among my people is

Ubayyi ibn kab Ka b.

(Ibn sad Sa d, Kitab

al-Tabaqat al-Kabir, Vol.2, p.441).

As a result he became

known as Sayyidul-Qurra, the "Master of the Readers".

Another tradition states that `Umar himself confirmed

that he was the best of the Muslims in the recitation of

the quran Qurčan (Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6, p.489). It is

therefore significant to find that numerous variant

readings existed between his and Zaid's text.

For example, in place of

wa yush-hidullaaha in Surah 2.204 he read wa

yastash-hidullaaha. He also omitted the words in khiftum

from Surah 4.101. Then again, in Surah 5.48 where the

standard reading is wa katabnaa `alayhim fiiha-"and we

inscribed therein for them (the Jews)"-the reading of

Ubayy was wa anzalallaahu alaa banii israiila Isra iila

fiiha-"and Allah sent down therein to the Children of

Israel". The variant was also recorded by at-Tabari

(6.153.24).

The evidences all show

that, prior to the endeavour by `Uthman to standardise

one codex for the purposes of obtaining uniformity of

reading, there were numerous different readings of the

quran Qurčan among the best known of the reciters. It

took time for the quran Qurčan to become a single text

and, as shall be seen, a second redaction was necessary

some centuries later to standardise the vocalised text

as well. One thing is quite obvious from all these

readings, however-there is no foundation for the Muslim

claim that the quran Qurčan presently read in the Muslim

world is an exact copy of the original text at the time

of Muhammad.

quran

4. Missing Passages of

the Qurčan Text

quran

The Mushaf: An Incomplete

Record of the Qurčan Text

During the Battle of

Yamama shortly after Muhammad's death a number of the

qurra, reciters of the quran Qurčan, perished and, as

has been seen already, some passages of the text are

said to have disappeared with them. No one else is said

to have known these texts and it must be assumed that

they passed away with them. There are many other records

to show that individual verses and, at times, whole

passages are missing from the quran Qurčan in its

standardised form. These all serve to indicate that the

mushaf of the quran Qurčan, as Muslims read it today, is

in fact an incomplete record of the original handed down

to them. `Abdullah ibn `Umar, in the earliest days of

Islam, had this to say on the subject:

Let none of you say "I

have acquired the whole of the quran Qurčan". How does

he know what all of it is when much of the quran Qurčan

has disappeared? Rather let him say " I have acquired

what has survived". (As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii `Ulum quran

al-Qurčan, p.524).

There are many examples

that could be quoted but a selection of these should

suffice to prove the point. A typical case relates to a

verse which is said to have read:

The religion with Allah

is al-Hanifiyyah (the Upright Way) rather than that of

the Jews or the Christians, and those who do good will

not go unrewarded.

(As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii

`Ulum quran al-Qurčan, p.525).

It is said that this

verse at one time formed part of Suratul-Bayyinah (Surah

98). This is quite possible as it fits well into the

context of the short surah which contains, in other

verses, some of the words appearing in the missing text,

such as din (religion, v.5), aml aml (to do, v.7) and

hunafa (upright, v.4). It also contrasts the way of

Allah with the beliefs of the Jews and Christians.

It is also interesting to

note that, whereas the standard text of Surah 3.19 today

reads innadiina `indallaahil-Islaam-"the religion before

Allah is al-Islam (i.e. the Submission)", Ibn masud

Mas ud read in place of al-Islam the title

al-Haniffiyah, i.e. "the Upright Way". At the beginning

of Muhammad's prophetic mission there were a number of

people in Arabia who disclaimed the worship of idols and

called themselves hunafa, specifically meaning those who

follow the upright way and who scorn the false creeds

surrounding them.

It is possible that this

was the initial name of of the specific faith which

Muhammad later called Islam as his religion took on its

own special identity and as his followers specifically

came to be called Muslims, those who submit to Allah.

This would account for the subsequent lapse of the title

in the quran Qurčan and the omission of the text which

is said to have been part of the text.

There are further

evidences of whole surahs said to be missing from the

quran Qurčan in its present form. Abu Musa ashari

Al- Ashari, one of the earliest authorities on the quran

Qurčan text and a companion of Muhammad, is reported to

have said to the qurra in Basra:

We used to recite a surah

which resembled in length and severity to (Surah) baraat

Bara'at. I have, however, forgotten it with the

exception of this which I remember out of it: "If there

were two valleys full of riches, for the son of Adam, he

would long for a third valley, and nothing would fill

the stomach of the son of Adam but dust". (Sahih Muslim,

Vol.2, p.501).

The one verse he said he

could recall is one of the well-known texts said to be

missing from the quran Qurčan. Abu Musa went on to say:

We used to recite a surah

similar to one of the Musabbihaat, and I no longer

remember it, but this much I have indeed preserved: "O

you who truly believe. Why do you preach that which you

do not practise? (and) that is inscribed on your necks

as a witness and you will be examined about it on the

Day of Resurrection".

(As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii

`Ulum quran al-Qurčan, p.526).

The tradition as here

quoted follows the record of it in the Sahih Muslim

where it is set out after the statement about the surah

resembling the ninth surah and containing the verse

about the son of Adam (Vol.2, p.501). The Musabbihaat

are those surahs of the quran Qurčan (numbers 57, 59,

61, 62 and 64) which begin with the words Sabbahu (or

yusabbihu) lillaahi maa fiis-samaawaati wal-ardth-"Let

everything praise Allah that is in the heavens and the

earth". These are records from the most authoritative of

Islamic sources and they indicate very clearly that the

quran Qurčan in its present form is somewhat incomplete.

quran

Specific Verses Said to

be Missing from the Qurčan

Much is said in the

Hadith literature about the missing verse about the "son

of Adam". The tradition is so widely reported that it

must be authentic in its basic details. As-Suyuti

records a number of these to show how well-known it was,

one of which reads:

Abu Waqid laithii al-La ithii

said, "When the messenger of Allah (saw) received the

revelation we would come to him and he would teach us

what had been revealed. (I came) to him and he said `It

was suddenly communicated to me one day: Verily Allah

says, We sent down wealth to maintain prayer and deeds

of charity, and if the son of Adam had a valley he would

leave it in search for another like it and, if he got

another like it, he would press on for a third, and

nothing would satisfy the stomach of the son ofAdam but

dust, yet Allah is relenting towards those who relent'."

(As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii

`Ulum quran al-Qurčan, p.525).

This record is followed

by a similar tradition recorded by Ubayy ibn kab Ka b

which gives the verse in much the same words, except

that in this case the companion expressly stated that

Muhammad had quoted this verse as part of the quran

Qurčan text which he had been commanded to recite.

Following this is the tradition of Abu Musa, similar to

the record in the Sahih Muslim, which states that the

verse was from a surah resembling suratul baraah

Suratul-Bara ah in length. In this case, however, Abu

Musa is not said to have forgotten it but rather that it

had subsequently been withdrawn (thumma rafaat rafa at-"then

it was taken away"), the verse on the greed of Adam

alone being preserved (As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan, p.525).

Abu Ubaid in his work

Fadhail quran al-Qurčan and Muhammad ibn Hazm in his

Kitab al-Nasikh wal wa l Mansukh both recorded this

verse as well but alleged that it was part of a surah

that was later abrogated and duly withdrawn. Nonetheless

it remained in the memory of many reciters as a portion

of the original quran Qurčan text.

Another very well-known

passage said to be missing from the quran Qurčan relates

to the "stoning verses" initially brought to the

attention of the growing Muslim community by `Umar, the

second Caliph of Islam. They state that Muhammad once

ordered all adulterers to be stoned to death in contrast

with the statement in Surah 24.2 that they should be

lashed with a hundred strokes. `Umar is said to have

drawn the attention of the Muslim community to this

passage from the mimbar (pulpit) in the mosque of Medina

towards the end of his life. He is reported to set the

matter before those gathered before him as follows:

Allah sent Muhammad (saw)

with the Truth and revealed the Holy Book to him, and

among what Allah revealed, was the Verse of the Rajam

(the stoning of married persons, male and female, who

commit adultery) and we did recite this verse and

understood and memorized it. Allah's Apostle (saw) did

carry out the punishment of stoning and so did we after

him. I am afraid that after a long time has passed,

somebody will say, "By Allah, we do not find the verse

of the Rajam in Allah's Book", and thus they will go

astray by leaving an obligation which Allah has

revealed. (Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.8, p.539).

`Umar was clearly

persuaded that this verse was originally a part of the

quran Qurčan as revealed to Muhammad and was concerned

that over a period of time it would be forgotten by the

next generation of Muslims. In another record of this

incident it is said that `Umar added: "Verily stoning in

the Book of God is a penalty laid on married men and

women who commit adultery if proof stands, or pregnancy

is clear, or confession is made" (Ibn Ishaq, Sirat

Rasulullah, p.684). Both of these records add that `Umar

mentioned another missing verse which was once part of

the kitabullah (viz. the quran Qurčan) which the

earliest of Muhammad's companions used to recite, namely

"O people! Do not claim to be the offspring of other

than your fathers, as it is disbelief on your part to be

the offspring of other than your real father" (Sahih al-Bukhari,

Vol.8, p.540). There are indeed many Hadith records

which record that Muhammad during his lifetime duly

ordered the stoning of adulterers:

Ibn Shihab reported that

a man in the time of the Apotle of Allah (saw)

acknowledged having committed adultery and confessed it

four times. The Apostle of Allah (saw) then ordered and

he was stoned. (Muwatta Imam Malik, p.350).

The difference between

this tradition and the quranic Qurčanic text quoted on

giving adulterers a hundred stripes has led to much

discussion among Muslim commentators. They generally

concluded that, as `Umar had so much to say about the

missing verse, it must have been part of the original

text but had possibly been withdrawn. Nevertheless it

was presumed that the teaching and prescription found in

the verse remained binding as part of the sunnah, the

"example" of the Prophet. They decided that stoning of

adulterers was the penalty for married men and women who

commit adultery but that a hundred lashes was the

punishment for a single person who cohabited with a

married person. In the early days Muslim scholars

struggled with the implications of the many traditions

which stated very clearly that certain passages were

missing from the quran Qurčan.

Nonetheless `Umar was

quite statisfied that the order to stone those guilty of

adultery was indeed a part of the original text as

appears from this particular tradition of the same

incident:

See that you do not

forget the verse about stoning and say: We do not find

it in the Book of Allah; the Apostle of Allah (saw) had

ordered stoning and we too have done so after him. By

the Lord Who holds possession of my life, if people

should not accuse me of adding to the Book of Allah, I

would have transcribed therein: Ash-shaikhu wash-shaikhatu

ithaa zanayaa faarjumuu humaa. We have read this verse.

(Muwatta Imam Malik,

p.352).

These traditions, among

many others of a similar nature, all give the impression

that the quran Qurčan, once it was compiled into a

single text at the end of Muhammad's life, was

incomplete. Numerous passages, although not entirely

forgotten by the companions of the Prophet, had

nevertheless fallen out of the text of the book as it

was generally recited by the Muslims and are no longer a

part of it. While they do not appear to affect the

teaching of the quran Qurčan as it stands today, they

nevertheless do witness against its complete

authenticity.

sabat i ahruf

5. Sab at-I-Ahruf: The

Seven Readings

sabat i ahruf

The Sab at-I-Ahruf in the

Hadith Literature

`Uthman succeeded in

standardising a single written text of the quran Qurčan

but, as the pronunciation of words and clauses was not

reflected in the earliest manuscripts, the quran Qurčan

was still read in different ways. No vocalisation of the

written text existed at that time and so the script (as

much of written Arabic does today) was transcribed with

consonants only. Vowel points were only added much

later. At the same time a tradition had been recorded

that the Prophet himself had stated that the quran

Qurčan was in fact sent down with more than one form of

recitation:

The quran Qurčan has been

revealed to be recited in seven different ways, so

recite of it that which is easier for you.

(Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6,

p.510).

This statement concludes

an incident where `Umar one day heard Hisham ibn Hakim

reciting Suratul-Furqan in a way very different to that

which he had learnt it. In his typical impulsiveness he

intended to spring upon him but controlled himself until

Hikam had finished his reading. `Umar immediately

confronted him with being a liar when he claimed that he

had learned his recitation directly from Muhammad

himself. When they approached the Prophet for a decision

he confirmed both their readings, adding the above

statement that the quran Qurčan had been revealed alaa

sabati sab ati ahruf, "in seven readings". A similar

tradition stating that the quran Qurčan was originally

sent down in seven different forms reads as follows:

Ibn `Abbas reported

Allah's Messenger (may peace be upon him) as saying:

Gabriel taught me to recite in one style. I replied to

him and kept asking him to give more (styles), till he

reached seven modes (of recitation). Ibn Shihab said: It

has reached me that these seven styles are essentially

one, not differing about what is permitted and what is

forbidden.

(Sahih Muslim, Vol.2,

p.390).

Another tradition states

that Ubayy ibn kab Ka b recalled an occasion where

Muhammad reported that Jibril (Gabriel) had one day

informed him that Allah had commanded that the quran

Qurčan be recited in only one dialect, to which Muhammad

replied that his people were not capable of this. After

some negotiation the angel informed him that Allah had

allowed the Muslims to recite the quran Qurčan in seven

different ways and that each one would be correct (Sahih

Muslim, Vol.2, p.391).

Apart from these

traditions there are no records to define exactly what

these seven different forms of reading were. As a result

numerous different explanations have been given, some

saying that this was to accommodate the different

dialects of the Arab tribes and others that they were

seven distinct forms conveyed to the centres of Islam by

approved readers in the second century of Islam. Abu

`Amr is said to have taken one of these to Basrah, Ibn

Amir took another to Damascus, and so on (Sunan Abu

Dawud, note 3365, Vol.3, p.1113). No one can possibly

say what they were, however, as nothing more is said in

the Hadith literature than that they were confined to

differences in dialect and pronunciation.

It is important to note

that these are a different type of variant reading to

those which `Uthman suppressed. The records which have

been kept of the latter were, as has been seen already,

of words, clauses and other real differences in the text

itself. In the case of the sabat i ahruf sab at-i-ahruf,

however, the distinction was confined to finer points of

pronunciation and expression of the text. `Uthman was

well aware of the different types and he obviously

wanted to eliminate both of them. To erase the textual

differences he simply chose Zaid's codex in preference

to the others and ordered that they be burnt. To deal

with the dialectal variants, on the other hand, he

ordered said Sa id ibn al-As and two others from the

Quraysh to amend Zaid's text where necessary to confine

the text to their dialect. The following impression of

his action is very informative:

He transcribed the texts

(suhuf) into a single codex (mushaf waahid), he arranged

the suras, and he restricted the dialect to the

vernacular (lugaat) of the Quraysh on the plea that it

(quran Qurčan) had been sent down in their tongue.

(As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii

`Ulum quran al-Qurčan, p.140).

He succeeded eminently in

eliminating the real differences in the text between the

different codices by destroying all but one, but he was

unable to eradicate the differences in dialect as these

could not be defined in a written text that had no vowel

points. It is these alone that the sabat i ahruf

sab at-i-ahruf are said to have affected. Muslim

scholars and writers in modern times often attempt to

blur the distinction by suggesting that the only variant

readings that existed were in the pronunciation of

different dialects (lugaat) and that, although `Uthman

sought to suppress them, the Prophet of Islam himself

had originally authorised them. It is obvious, however,

that the prime purpose of the Caliph's action was to

eliminate serious differences in the actual text of the

quran Qurčan and that he could not, in fact, have

succeeded in deleting the dialectal variations (which

would have been negligible in comparison with the

textual variants).

Abu Dawud records a

selection of the latter type in his Kitab al-Huruf wa

qiraat al-Qira at ("The Book of Readings and

Recitation"). These three examples show how the

differences in pronunciation affected the text:

Shahr b. Hawshab said: I

asked Umm Salamah: How did the Apostle of Allah (may

peace be upon him) read this verse: "For his conduct is

unrighteous" (innaha `amalun ghairu salih)? She replied:

He read it: "He acted unrighteously" (innaha `amila

ghaira salih).

(Sunan Abu Dawud, Vol.3,

p.1116).

Ibn al-Mussayab said: The

Prophet (may peace be upon him), Abu Bakr, `Umar and

`Uthman used to read maliki yawmil din yawmi l-din

("Master of the Day of Judgment"). The first to read

maliki yawmil yawmi l diin was Marwan. (Sunan Abu Dawud,

Vol.3, p.1119).

Shaqiq said: Ibn masud

Mas ud read the verse: "Now come thou" (haita laka).

Then Shaqiq said: We read it, hitu hi tu laka ("I am

prepared for thee"). Ibn masud Mas ud said: I read it as

I have been taught, it is dearer to me.

(Sunan Abu Dawud, Vol.3,

p.1120).

In each case the variant

is found solely in the vowelling of the text and would

not have been reflected in the consonantal text

transcribed by `Uthman. It can clearly be seen that this

type of variant reading has virtually no effect on the

text or its meaning, unlike the other type which covers

whole words and clauses found in some codices and not in

the others. It was to be some centuries before serious

attention was given to actually defining the sabat i

ahruf sab at-i-ahruf, the "seven different readings".

The Period of Ikhtiyar

Until Ibn Mujahid

For the next three

centuries after `Uthman there were considerable

differences in the recitation of the quran Qurčan as a

result of his inability to eliminate the dialectal

variants, but the differences were confined to these

alone. This was a time of ikhtiyar, a period of "choice"

when Muslims were free to read the quran Qurčan in

whichever dialect they chose on the strength of the

tradition that there were seven legitimate ways in which

the quran Qurčan could be recited. During this period

until the year 322 AH (934 AD), all scholars of the

quran Qurčan agreed that such recitations were valid

although no one could define exactly what the seven

readings were. They would be at the discretion of anyone

who attempted to specify them.

In that year, however,

the well-known authority on the quran Qurčan at Baghdad,

Ibn Mujahid, took it upon himself to resolve the issue.

He had considerable influence with Ibn `Isa and Ibn

Muqlah, two of the wazirs (ministers) in the Abassid

government of the day. Through them he managed to

establish an official limitation on the permissible

readings of the quran Qurčan. He wrote a book titled al

qiraat Al-Qira at sabah as-Sab ah ("The Seven

Recitations") and in it he established seven of the

readings current in the Muslim world as canonical and

declared the others shadhdh ("isolated") and no longer

legitimate. He gave no source of authority for his

decision and it appears it was entirely his own

discretion which guided him.

The seven readings now

authorised were those of Nafi (Medina), Ibn Kathir

(Mecca), Ibn `Amir (Damascus), Abu `Amr (Basrah), Asim,

Hamzah and al-Kisai (Kufa). In each case there were

certain recognised transmitters who had executed a

recension (riwayah) of their own of each reading and two

of these, those of Warsh (who revised Nafi's reading)

and Hafs (who revised asims Asim's) eventually gained

the ascendancy as the others generally fell into disuse.

Warsh's riwayah has long been used in the Maghrib (the

western part of Africa under Muslim rule, namely

Morocco, Algeria, etc) mainly because it was closely

associated with the Maliki school of law but it is the

riwayah of Hafs that has gradually gained almost

universal currency in the Muslim world. This has

particularly been so since the printing of the quran

Qurčan became commonplace.

Ibn Mujahid's

determination to canonise only seven of the readings

current in the Muslim world of his day was upheld by the

Abbasid judiciary. Very soon after his decree a scholar

named Ibn Miqsam was publicly forced to renounce the

widely-held opinion that any reading of the basic

consonantal outline was acceptable as long as it

contained good Arabic grammar and made good sense. The

period of ikhtiyar duly closed with Ibn Mujahid's

action. He did to the vocalised reading of the quran

Qurčan what `Uthman had done to the consonantal text

many centuries earlier. Just as the Caliph had destroyed

the different codices so this scholar outlawed all

dialectal readings in use except seven. So likewise,

just as the text standardised by `Uthman cannot be

regarded as a perfect copy of the quran Qurčan exactly

as it was delivered by Muhammad because it only

standardised the text of one redactor at the Caliph's

personal discretion, so the seven readings canonised by

Ibn Mujahid cannot be accepted as an exact reflection of

the sabat i ahruf sab at-i-ahruf as they were likewise

arbitrarily chosen by the redactor according to his own

preference and judgment.

It is obvious that no one

with any real authority can say precisely what the seven

different readings referred to in the Hadith actually

were. A very good example of the confusion caused in

subsequent generations about these readings is found in

the following quote attributed to Abu al-Khair ibn

al-Jazari prior to Ibn Mujahid's declarations:

Every reading in

accordance with Arabic, even if only remotely, and in

accordance with one of the `Uthmanic codices, and even

if only probable but with an acceptable chain of

authorities, is an authentic reading which may not be

disregarded, nor may it be denied, but it belongs to al

ahruful sabat al-ahruful-sab at (the seven readings) in

which the quran Qurčan was sent down, and it is

obligatory upon the people to accept it, irrespective of

whether it is from the seven Imams, or from the ten, or

yet other approved imams, but when it is not fully

supported by these three (conditions), it is to be

rejected as dhaifah dha ifah (weak) or shaathah

(isolated) or baatilah (false), whether it derives from

the seven or from one who is older than them.

(As-Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii

`Ulum quran al-Qurčan, p.176).

This statement shows how

impossible it was to define the seven different

readings. Any good reading was automatically considered

to be one of them, not because it could be proved to

belong to them, but because of other factors-its isnad

(chain of authorities), its consistency with the

`Uthmanic consonantal text, and its compliance with

proper Arabic grammar. The decision rested purely on

matters of discretion.

Contrary to the

oft-stated Muslim sentiment that the quran Qurčan as it

stands today is an exact replica of the one said to be

inscribed on the Preserved Tablet in heaven, it is

obvious that the book went through a long period in

which distinctions in both the actual text and

thereafter in dialectal reading were eliminated in the

interests of obtaining a single text. The quran Qurčan

became standardised into the form in which it is found

today, mainly through the actions of `Uthman and Ibn

Mujahid respectively but also through other means such

as the gradual lapse of most of the readings accepted by

the latter scholar. The book only contains a uniform,

defined text because certain Muslims of earlier times

made it their express purpose to reduce it to a single

text upon which the whole Muslim world could be united.

The evidences show, however, that whole passages are now

missing from certain surahs, that considerable numbers

of variant readings existed in the original codices, and

that a host of different dialectal readings survived

until some three centuries later until these were

reduced to seven. Only the printing of the quran Qurčan

has finally given the Muslim world a single, unvaried

text.

There is even evidence to

show that some time after `Uthman's action to

standardise the mushaf, the written text of the quran

Qurčan, certain amendments were made to Zaid's text.

Under the heading Bab: Ma Ghaira al-Hajjaj fii Mushaf

`Uthman ("Chapter: What was Altered by al-Hajjaj in the

`Uthmanic Text") Ibn Abi Dawud lists eleven changes made

by the governor of Iraq during the caliphate of `Abd

al-Malik many decades after the death of `Uthman. His

narrative begins as follows:

Altogether al-Hajjaj ibn

Yusuf made eleven modifications in the reading of the `Uthmanic

text. .. In al-Baqarah (Surah 2.259) it originally read

Lam yatasanna waandhur, but it was altered to Lam

yatassanah ... In maida al-Ma ida (Surah 5.48) it read

Shar yaatan ya atan wa minhaajaan but it was altered to

shir `atawwa minhaajaan. (Ibn Abi Dawud, Kitab al-Masahif,

p.117).

The whole section

continues to name each of the changes made by the

governor in what appears to have been a further minor

recension of the text. Interestingly each one of the

readings amended was also originally the reading of

Ubayy ibn kab Ka b as well.

There can be little doubt

that the quran Qurčan has generally survived intact and

that its present text is a relatively authentic

reproduction of the book as it was originally delivered.

There is no justification, however, for the Muslim dogma

that nothing in it, to the last dot or letter, has ever

been changed or amended, or that any portion of it has

since been lost or omitted.

quran

6. The Early Surviving

Quran Manuscripts

The Initial

Development of the Text

Numerous early

manuscripts of the quran Qurčan from approximately one-

hundred-and-fifty years after Muhammad's death have

survived though none is in complete form. Large portions

have been preserved intact but on the whole only

fragments exist. It was generally assumed, as it is

today, that the Arabic language was so familiar to its

speakers that vowelling of the text was not necessary. A

number of consonants were not distinguished from one

another either so that only seventeen were employed in

the very early texts. As time passed, however, the

similar consonants were separated by diacritical points

above or below the letters and vowelling soon followed

to clearly identify the reading of each text. Today

almost without exception printed quran Qurčans are fully

vocalised.

No form of dating appears

in the earliest manuscripts either so that the date and

place of origin of these texts is generally a matter of

conjecture. It was only in later centuries that the

calligrapher's name was disclosed in a colophon (usually

at the end of a text) together with the date and place

where the codex was transcribed. Unfortunately some

colophons in the early manuscripts are known to have

been forged so that accurate identification often

becomes almost impossible.

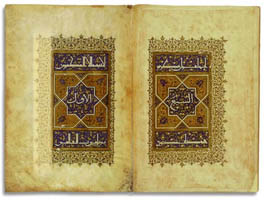

Even after vocalisation

became common some quran Qurčan manuscripts were

transcribed in the original form. A good example is the

superb text written in gold script on blue vellum which

survives almost intact from Kairouan in Tunisia where it

was originally inscribed in the late ninth or early

tenth century AD. It has been suggested that the

scribe's intention was to produce a work of great beauty

for commemorative purposes rather than for general

reading. This quran Qurčan was intended to be presented

to the Abbasid Caliph mamun al-Ma mun for the tomb of

his father, Harun ar-Rashid, at Mashad in Persia. For

some reason it never left Tunis and the bulk of it is

preserved in the National Library of Tunisia in the

city. A number of individual leaves are in private

collections.

The best indication of an

early manuscript's origin, however, is its script. A

number of different styles were used in the early days

and these went through various stages of development.

These factors help to determine the likely origin of any

particular text. Prior to the advent of Islam the only

proper script known to exist was the Jazm script. It had

a very formal and angular character and it was from this

style that the other famous early scripts developed. No

quran Qurčan fragment, however, is known to have been

written out in this form. The earliest quran Qurčan

script known was employed in Arabia and is called the al

mail al-Ma il script. It was first utilised in Medina.

It is unique in that it uses vertical letters which are

written at a slight angle. The very name means "the

slanting" script and its upright form resulted in the

early manuscripts being produced in a vertical format

similar to that used for most books today. Only a few

pages and fragments and, in a few cases, whole portions

of the quran Qurčan are known to have survived yet they

are almost certainly the oldest in existence. They date

not earlier than about one hundred and fifty years after

the death of Muhammad. A sign of their early origin is

the fact that no vowel strokes or diacritical points

were used in the text and no verse counts or chapter

headings were recorded.

The second early script

originating from Medina was the Mashq, the "extended"

style which was used for a few centuries. It was the

first to use a horizontal form and had a cursive and

somewhat leisurely style. The most common early script,

however, was the Kufi, more properly known as al-Khatt

al-Kufi. Its title does not indicate its form but rather

its place of origin, namely Kufa in Iraq where Ibn masud

Mas ud's codex had been so highly prized until its

destruction at `Uthman's direction. It took some time to

become predominant but, when it did, it became

pre-eminent for three centuries and many superb texts

survive.

Like the Mashq script it

employed a horizontal, extended style and as a result

most of the codices compiled were oblong in format. In

time it became supplemented with diacritical marks and

vowel strokes. No Kufic quran Qurčans are known to have

been written in Mecca and Medina in the first two

centuries when the al mail al-Ma il and Mashq scripts

were most regularly used. Nonetheless most of the early

surviving quran Qurčan texts are written in Kufi script.

Another script which

derives from the Hijaz in Arabia is the Naskh, the

"inspirational" script. It took some time before it

became widely accepted but, when it did, it replaced

virtually all the others including the Kufi as the

standard form of transcribing the quran Qurčan. It

remains so until this day and virtually all quran

Qurčans printed and written out by hand since the

eleventh century are written in this form. It is easily

readable and also yields readily to artistic

calligraphy. One of the earliest quran Qurčans to use

this form which survives intact as a complete text is

the famous manuscript written out by Ibn al-Bawwab at

Baghdad in 1001 AD. It is now in the Chester Beatty

Library in Dublin in Ireland.

One other script amongst

a few which developed after the Naskhi is the Maghribi,

the "Western" script which, as its name indicates, comes

from the extreme western region of the traditional

Islamic world. It was first employed in Morocco and

Moorish Spain and is still used in the area to this day.

It is a very cursive script, not easy to read for those

unfamiliar with the Arabic language, but highly

attractive when written artistically.

The Topkapi and

Samarqand Codices

Despite the evidences