|

Introduction to New Testament Criticism

When either the Old or New Testament is read in

English, the reader needs to understand they are reading a

translation. The translation is based on manuscripts, copies of

copies, which were transmitted over time by humanity. Since the

original autograph does not exist, we depend on faithful

transmission of the text. Textual Criticism understands with the

human process of translation, there exists the potential of

transmittal errors. When either the Old or New Testament is read in

English, the reader needs to understand they are reading a

translation. The translation is based on manuscripts, copies of

copies, which were transmitted over time by humanity. Since the

original autograph does not exist, we depend on faithful

transmission of the text. Textual Criticism understands with the

human process of translation, there exists the potential of

transmittal errors.

The purpose of textual criticism is to restore as near as

possible the words of the autograph. This is done by examining

the evidence, the manuscripts, comparing the manuscript to

manuscript.

The New Testament manuscripts contrasted to the Old

Testament manuscripts has a greater quantity, closer to the date

of authorship but lower in quality. There are about 5400 Greek

New Testament manuscripts, which allows us to verify the

transmission of the Greek manuscripts.

The dynamic links between manuscripts, manuscript

transmission and textual criticism can clearly be illustrated in

the commonly known, Textus Receptus,

which is the Greek text used in the translation of the King

James bible of 1611.

Textual Criticism of the New Testament

In textual criticism of the New Testament, we need

to understand the role Greek New Testament manuscripts play.

Since the New Testament was written in Greek, the Greek

manuscripts are the closest point to the original autographs.

During the transmission process, variations occur, because

manuscripts are copied by hand, these copyist variations, then

copies of the manuscript over time. These variations allow us

to trace families of manuscripts because of similarities

contained with the documents.

Variations

Just what is a variation? The vast majority of variations have

very little impact on the meaning of the manuscript. A

variation is just what means, if one manuscript spells the word

different there is a variation. If one manuscript has different

punctuation, that is a variation.

To put these variations between manuscripts in

context, Paul Wagner writes,

“The verbal agreement between various New Testament manuscripts

is closer than between many English translations of the New

Testament and that the actual number of variants in the New

Testament is small (approximately 10 percent), none o which call

into question any major doctrine.

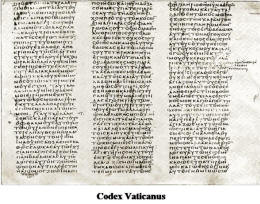

The greatest number of

variants are differences or errors in spelling. For example,

the author of Codex Vaticanus spells “John” with only one n

instead of the common spelling with two. This type of variant

makes no difference in the meaning of the text.

The second largest group

arises because of omissions of small Greek words or variations

in word order. For example, in Greek a person a person’s name

may or may not be preceded by an article (“the”). And the phrase

the good man could also be written in Greek as “the man, the

good one” although in English both phrases are translated “the

good man.” These types of variants also make no difference to

the meaning of the text.

Textual criticism’s goal is to reach back to the autograph,

examining the variations to determine, what exact words would

have been in the autograph.

Procedure for New Testament Textual

Criticism

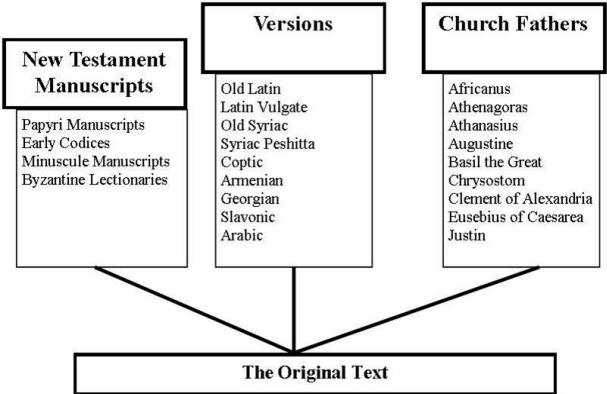

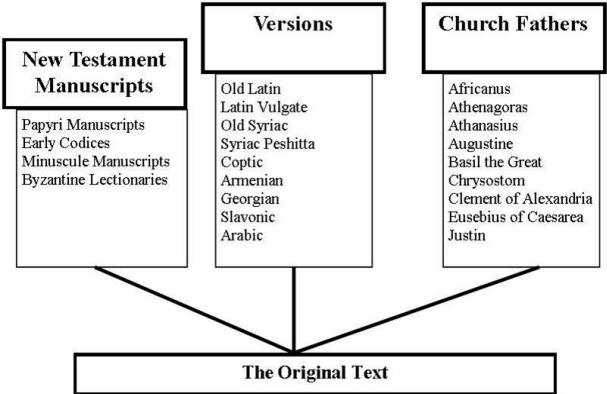

1. Collecting the evidence

Like the Old Testament, the purpose of Textual Criticism is to

try to restore as near as possible the original autograph, by

examining the manuscript evidence. So the procedure would be to

first to collect the available evidence. The three primary

sources of this evidence are:

1. New Testament Manuscripts

2. The writings of the Church Fathers

3. Early translation versions

2. Evidence evaluation

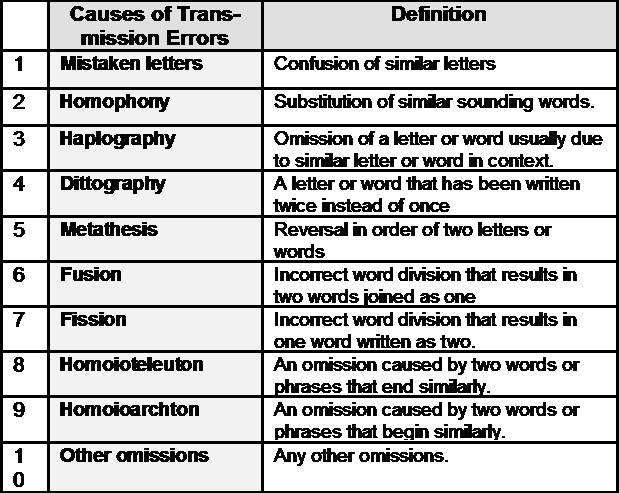

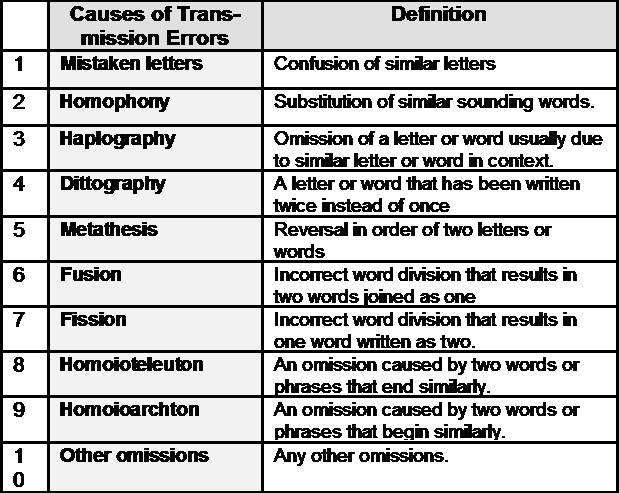

Human beings copied the Old Testament, and they also copied the

New Testament, the errors of Old Testament copyist are the same

as those in the New Testament.

3. Determine the most plausible

reading

There are six principles used to determine the most plausible

reading, when comparing the evidence of a verse.

1. Manuscripts must be weighed, not counted

2. Determine the reading that would most likely give rise to the

others.

3. The more distinctive reading is usually preferable.

4. The shorter reading is generally favored.

5. Determine which reading is more appropriate in its context

(examine literary contexts, grammatical or spelling errors,

historical context).

6. Examine parallel passages for any differences and determine

why they may appear.

History of New Testament Textual

Criticism

From the autographs, the New Testament spread

throughout the Greek speaking world, as manuscript copies were

made by the various growing Christian communities. As

Christianity became more established, copies of manuscripts

continued to be made, some more careful then others. As the

Christian faith reached the non-Greek speaking world,

translations of the New Testament scriptures also came into

existence.

The Latin Vulgate

One of the first languages, which the New and Old

Testaments were translated into was Latin, specifically Old

Latin, the official language of the Roman Empire. When

Constantine, the Roman Emperor became Christian (A.D. 312),

Christianity became the religion of the Roman Empire.

Accordingly, the Greek scriptures were translated into Old

Latin, since Latin was the official language of Rome. By A.D.

382, the variations of in the Old Latin translations reached an

unacceptable point.

In 382, Pope Damascus appointed Eusebius

Hieronymus, known as St. Jerome, the Biblical scholar of his

day to conform the Latin text with the Greek text. Jerome used

textual criticism, by comparing the Latin manuscripts to the

Greek manuscripts, making sure the Latin translation was in line

with the Greek, this process took 2-years (382-390). Bruce

Metzger, refers to the process of Jerome translation, which

later became known as the Vulgate (“common”).

“He used a relatively good Latin text as the basis for his

revision, and compared it with some old Greek manuscripts. He

emphasizes that he treated he current Latin text as

conservatively as possible, and changed it only where the

meaning was distorted.”

Jerome’s Vulgate NT

translation became the standard Bible for the Roman Empire for

the next 1000-years, despite the fact copyist were included in

the transmission of the Vulgate.

The Latin Bible was well

established in Europe as the official Bible, however the only

ones who could read and understand its message, were clergy and

those fluent in the ancient languages. Several events would

occur in the 15th century, which would change the

status quo of the Latin translation.

The Greek Text Revisited

The excessive

ecclesiastical control over catholic nations and abusive clergy

brought about a reformation movement, which was fueled by the

printing press developed by Johann Gutenberg (1398-1468), in

1466. Gutenberg printed the Latin Vulgate, but for the first

time the possibility of less expensive books (manuscripts)

became a reality.

On May 29th,

1453 Constantinople fell to the Turkish armies, this caused many

of the Greeks, who were part of the eastern church to flee to

the west with their Greek manuscripts. Until this time the

Latin Vulgate translations stood unchallenged as authority of

scripture for both the Catholic church and clergy. In Germany,

England and other European countries, movements to translate

scripture into vernacular languages began to take hold. Advances

in printing made Bibles more accessible available for the common

man. The rebirth of the scripture caused a need for a Greek

text of scripture. What

Erasmus’s Greek New Testament

Like Jerome a thousand

years earlier, translators could use the Vulgate, or they could

look at the available Greek manuscripts as the source of their

translation work. In Italy by 1471, there were two versions of

an Italian Bible, in Spain the Bible was translated in 1478, in

France 1487 and a Dutch version in 1477. A revival of scripture

had taken hold in Europe pitting many of its leaders against the

established Catholic Church. The Greek text of scripture had

yet to be published yet, this was about to change with

Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam ( 1466-1536), who is credited

preparing the first Greek text in 1516. Like Jerome a thousand

years earlier, translators could use the Vulgate, or they could

look at the available Greek manuscripts as the source of their

translation work. In Italy by 1471, there were two versions of

an Italian Bible, in Spain the Bible was translated in 1478, in

France 1487 and a Dutch version in 1477. A revival of scripture

had taken hold in Europe pitting many of its leaders against the

established Catholic Church. The Greek text of scripture had

yet to be published yet, this was about to change with

Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam ( 1466-1536), who is credited

preparing the first Greek text in 1516.

Erasmus was born the illegitimate son of a Dutch priest

and a physicians daughter. Both parents died at an early age,

his guardians sent him to a school in Hertogenbosch conducted by

the Brethren of the Common Life, a religious group which taught

the virtue of monastic life. Erasmus became a monk in the

Augustine order (1485-92).

Erasmus became known for his scholarship in Latin

and his disdain for corruption of the church. He was released

from his vows and went on to teach at Cambridge, where he saw he

need to learn Greek.

The Swiss printer Froben asked Erasmus to prepare a

copy of the Greek New Testament, which he agreed. Erasmus left

for Basel Switzerland in July 1515, to begin this work. The

publisher was in a rush to finish the project, knowing Cardinal

Ximenes was also preparing a Greek text for publication, later

known as the Complutum Polygot.

Erasmus had hoped to just find one Greek manuscript for

the whole volume and publish it along side his new Latin

translation this was not the case. He was saw the manuscripts

needed correction, he ended up using a half dozen Greek

Minuscule including Codex 1, a tenth century, which often agrees

with the earlier uncial texts, this he used least. The work was

completed in ten months and had hundreds of typographical

errors. These errors were corrected in later editions.

One of the early disputes about the work of Erasmus

was the verse I John 5:7-8, Erasmus did not include the words

“the Father, the Word and the Holy Ghost: and these three are

one. And there are three that bear witness in earth”. Erasmus

was accused of removing God’s word, Bruce Metzger records his

reply:

Erasmus replied that he had not found any Greek manuscripts

containing these words, though he had in the meanwhile examined

several others besides those on which he relied when first

preparing his text. In an unguarded moment Erasmus promised that

he would insert the Comma Johanneum, as it is called, in

further editions if a single Greek manuscript could be found

that contained the passage. At length such a copy was found

[now designated Greg. 61]—or was made to order! As it now

appears the Greek manuscript had probably been written in Oxford

about 1520 by a Franciscan friar named Froy (or Roy), who took

the disputed words from the Latin Vulgate. Erasmus stood by his

promise and inserted the passage in his third edition (1522),

but he indicated in a lengthy footnote his suspicions that the

manuscript had been prepared expressly in order to confute him.

Erasmus Greek Text had

five editions, Luther used the second edition in his translation

of the German Bible in 1522 and William Tyndale used the third

edition for his English translation. The fourth edition was the

superior work, the text had three parallel columns, the Greek

Text, the Latin Vulgate, and Erasmus’s own Latin translation.

Erasmus incorporated some of Cardinal Ximenes translation work

in his fourth edition seeing the advantages the Complutum

Polygot, Ximenes Greek translation. He used it to modify his

translation. His text became the standard text for about four

hundred years, though there were better.

Robert Estienne (1503-1559) (Stephanus)

Estienne is

also known as Stephanus in Latin, this Paris publisher published

four editions of the Greek New Testament (1546, 1549, 1550,

1551). The first three were prepared for the French government

in Paris, the fourth edition was after Robert Estienne made a

confession of his conversion to the Protestant faith.

In the first

and second editions, Robert Estienne used Erasmus’s work and

Cardinal Ximenes’s Complutum Polygot and combined their

readings. The third edition, included a apparatus with various

readings from 14 Greek manuscripts in the margins. The fourth

edition was of Estienne Greek text was flanked on both sides by

the Latin Vulgate and Erasmus’s Latin translation, this edition

is also the first to appear with modern verse divisions.

Theodore de Beza (1519-1605)

Theodore de Beza succeeded

Calvin in Geneva as the leader of the Reformed Protestant

movement. Early in his life, his family wanted him to be a

priest, he however choose to be married, and secretly married

Claudine Desnoz in 1548. At twenty-nine he renounced the

Catholic faith and went to Geneva where he publicly married

Claudine Desnoz. He published nine editions of the Greek New

Testament during his life. Beza text was very similar to

Stephanus fourth edition (1551).

The work of

Erasmus, Estienne and Beza would be the underlying Greek which

would be used in the King James bible and every English Bible

until 1881.

|

|

The John Rylands Fragment John 18:31-33 (117-138 AD)

The earliest known copy of any portion of the New

Testament is from a papyrus codex (2.5 by 3.5 inches).

It dates from the first half of the second century A.D.

117-138. (P.52)The papyrus is written on both

sides and contains portions of five verses from the

gospel of John (18:31-33,37-38). Because this fragment

was found in Egypt a distance from the place of

composition (Asia Minor) it demonstrates the chain of

transmission. The fragment belongs to the John Rylands

Library at Manchester, England

|

|

|

Chester Beatty Papyri (250 AD)

This important papyri consists of three codices and

contains most of the New Testament. (P.45, P.46, P.47).

The first codex(P.45) has 30 leaves (pages) of

papyrus codex. Two from Matthew, two from John, six from

Mark, seven from Luke and thirteen from Acts, originally

there were 220 pages measuring 8x10 inches each. (P.46)The

second codex has 86 leaves 11x6.5 inches from an

original, which contained 104 pages of Paul’s epistles.

P.47 is made of 10 leaves from Revelation

measuring 9.5 by 5.5 inches, there were 32 leaves in

originally, chapters 9:10-17:2 remain. P.47 generally

agrees with the Alexandrian text of Codex Sinaiticus (a)))). |

|

|

Bodmer Papyri (200 AD)

Dating from 200 A.D. or earlier the Bodmer Papyri

Collection (P.66,P.72,P.75) P.66

104-leaves containing the Gospel of John 1:1-6:11,

6:35-14:26, 14-21. The text is a combination of Western

and Alexandrian Text types, twenty alterations belong to

the Western family text type. This papyri was prepared

by four scribes and was part of a private collection, it

measured 6 x 5 ¾ inches and is affiliated with the

Alexandrian text tradition. P.72 has the earliest

know copy of Jude, I Peter, and 2 Peter also contains

other Canonical and apocryphal books. P.72 measures 6 x

5.75 inches. P.75 is 102 pages measuring 10.25 by

5.33 inches. It contains most of Luke and John dated

between A.D. 175 and 225. P. 75 has the earliest known

copy of Luke, the text is very similar to the Codex

Vaticanus. (B)

|

|

|

CODEX SINATICUS (340 AD) (a)

Unical Text)

Considered by many, to the most important witness to the

Greek text of the New Testament dated in the 4th

century. Sinaiticus is highly valued because of its

age, accuracy and completeness. Found at St. Catherine’s

monastery at Mt. Sinai by Von Tischendorf (1815-1874),

it was acquired for the Czar of Russia. Sinaiticus

contains over 1/2 of the Old Testament (LXX) and all of

the new except for Mark 16:9-20 and John 7:53-8:11..

Also contains the Old Testament Apocrypha. Sinaiticus is

written on 364.5 pages measuring 13.5 by 14 inches. The

material is good vellum made from antelope skins.

Sinaticus was purchased by the British government for

$500,000 in 1933. The type text is Alexandrian with

strains of Western.

|

|

|

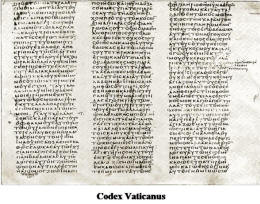

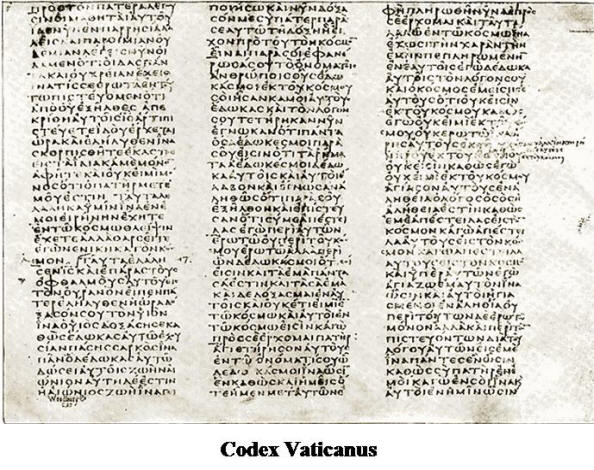

Codex Vaticanus (325-350 AD) (B) (Unical Text)

Vaticanus was written in the middle of the 4th century

and was not know to textual scholars until 1475 when it

was catalogued in the Vatican Library. For the next

400-years scholars were prohibited from studying it. It

includes most of the LXX version of the Old Testament

and most of the New. It contains 759 leaves measuring 10

by 10.5 inches. In 1890, a complete photographic

facsimile was made available. Missing from the Codex

Vaticanus is Hebrews 9:14 to the end of the New Testament and

I Timothy through Philemon, some of the OT Apocrypha is

included. Mark 16:9-20 and John

7:53-8:11 were omitted intentionally

from the document. Vaticanus is owned by the Roman

Catholic Church and is housed in the Vatican Library,

Vatican City. Vaticanus is considered an excellent

example of Alexandrian script. |

|

Like Jerome a thousand

years earlier, translators could use the Vulgate, or they could

look at the available Greek manuscripts as the source of their

translation work. In Italy by 1471, there were two versions of

an Italian Bible, in Spain the Bible was translated in 1478, in

France 1487 and a Dutch version in 1477. A revival of scripture

had taken hold in Europe pitting many of its leaders against the

established Catholic Church. The Greek text of scripture had

yet to be published yet, this was about to change with

Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam ( 1466-1536), who is credited

preparing the first Greek text in 1516.

Like Jerome a thousand

years earlier, translators could use the Vulgate, or they could

look at the available Greek manuscripts as the source of their

translation work. In Italy by 1471, there were two versions of

an Italian Bible, in Spain the Bible was translated in 1478, in

France 1487 and a Dutch version in 1477. A revival of scripture

had taken hold in Europe pitting many of its leaders against the

established Catholic Church. The Greek text of scripture had

yet to be published yet, this was about to change with

Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam ( 1466-1536), who is credited

preparing the first Greek text in 1516.