|

Introduction of the New Testament Canon

For

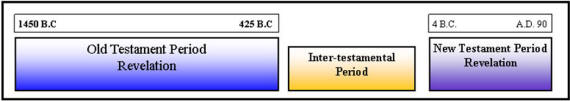

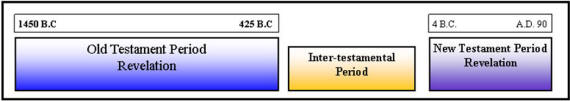

Christians today, their Bible has an Old and New Testament; both

testaments are a collection of books revealed over time. The

Old Testament was revealed over a thousand year period, 1450

B.C. to 425 B.C.; the New Testament is separated from the New

Testament by a 450-year period known as the Inter-testimonial

period. The New Testament, unlike the Old was revealed over

a much shorter time, a sixty-year period, from A.D. 33 to 100. For

Christians today, their Bible has an Old and New Testament; both

testaments are a collection of books revealed over time. The

Old Testament was revealed over a thousand year period, 1450

B.C. to 425 B.C.; the New Testament is separated from the New

Testament by a 450-year period known as the Inter-testimonial

period. The New Testament, unlike the Old was revealed over

a much shorter time, a sixty-year period, from A.D. 33 to 100.

By the time of Jesus, the Old Testament canon was

closed 450-years earlier. The question many people have is how

did the New Testament find itself placed alongside the books of

the Old Testament? In addition, how did the books in the

New Testament get included in the canon?

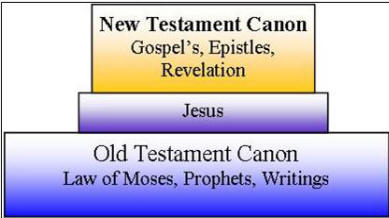

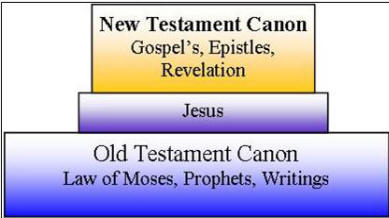

First, the any Bible student needs to understand the

Old Testament is the foundation of the New Testament. Jesus the

Messiah is the fulfillment of prophecies of the Old Testament

canon. The Messiah’s death and the establishment of a New

Covenant is a chief focus of the Old Covenant and its

canon. The Messiah would come, suffer and die for the sins of

the world; through the Messiah’s death, God would establish a

New Covenant. The New Covenant would establish an eternal

relationship between God and fallen humanity.

The New Testament Canon confirms and testifies to

the life of Jesus the Messiah, who established the New Covenant

in accordance to the Old Testament canon. The New Testament has

several divisions. First, the Gospels, they reveal the

life, ministry, and teachings of Jesus the Messiah. Second,

history, known as the Book of Acts records the history of

the early church after the ascension of Christ. Thirdly, the

Epistles are letters of instruction, from Apostles to the

churches and church leaders in the early church. Finally, the

Apocalypse or Revelation describes the final events

leading to the return of Jesus the Messiah.

Therefore when discussing the New Testament canon,

we need to understand its dependence on Old Testament canon.

For example, half the verses of the book of Revelation have a

direct or indirect reference to verses in the Old Testament.

The Gospels and Epistles constantly refer to the Old Testament.

The Old Testament

foundation

The death of Jesus the Messiah was

event foretold hundreds of years before his birth. His death was

payment for sins, as typified in the Old Testament sacrificial

system. His death established the New Covenant, the

basis of the revealed “Scripture” in the New Testament. The

word “testament” originates from the Greek word for “covenant”.

The basis of the New Testament is the

atoning death of Messiah, the New-Covenant is established on

his death, the Church is the inclusion of the Gentiles as part

of God’s people, grafted into the covenant blessings of Israel

(Romans11:20-22).

1. Messiah’s death

Isaiah foretold the death of Messiah, who would die for the sins

of the world 700-years before His birth. Daniel foretold the

exact month, year and day of Messiah death (Daniel 9:24-27).

13 Behold, My Servant shall deal prudently; He shall be

exalted and extolled and be very high10 Yet it pleased the Lord

to bruise Him; He has put Him to grief. When You make His

soul an offering for sin, He shall see His seed, He shall

prolong His days, And the pleasure of the Lord shall prosper in

His hand. 11 He shall see the labor of His soul, and be

satisfied. By His knowledge My righteous Servant shall

justify many, For He shall bear their iniquities. Isaiah

52:13,53:10-11

2. The New Covenant

Jeremiah wrote 600 years before the birth of Jesus about the

coming of greater covenant, greater then the Mosaic covenant,

with this Covenant iniquity will be forgiven, and sins

forgotten. This covenant will be relational, Israel will

be called “my people”, and the laws will be in the hearts and

minds of the Lord’s “people”. Into this Covenant the Gentiles

were included.

31 "Behold, the days are coming, says the Lord, when I will make

a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of

Judah 32 not according to the covenant that I made with their

fathers in the day that I took them by the hand to lead them out

of the land of Egypt, My covenant which they broke, though I was

a husband to them, F23 says the Lord. 33 "But this is the

covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those

days, says the Lord: I will put My law in their minds, and write

it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be

My people. 34 "No more shall every man teach his neighbor, and

every man his brother, saying, 'Know the Lord,' for they all

shall know Me, from the least of them to the greatest of them,

says the Lord. For I will forgive their iniquity, and their sin

I will remember no more." Jeremiah 31:31-34

3. Gentiles receive the light of the Gospel.

Isaiah wrote of the coming

of the righteous servant, who would bring justice to the

Gentiles (nations). The servant’s death (Isaiah 53:11) will be a

covenant and light to the Gentiles. After the death of Jesus,

He established his church to carry the gospel to the nations,

offering his atoning death to the lost. (Matthew 28:19)

1 "Behold! My Servant whom I uphold, My Elect One in whom My

soul delights! I have put My Spirit upon Him; He will bring

forth justice to the Gentiles. 2 He will not cry out, nor raise

His voice, Nor cause His voice to be heard in the street. 3 A

bruised reed He will not break, And smoking flax He will not

quench; He will bring forth justice for truth. 4 He will not

fail nor be discouraged, Till He has established justice in the

earth; And the coastlands shall wait for His law." 5 Thus says

God the Lord, Who created the heavens and stretched them out,

Who spread forth the earth and that which comes from it, Who

gives breath to the people on it, And spirit to those who walk

on it: 6 "I, the Lord, have called You in righteousness, And

will hold Your hand; I will keep You and give You as a

covenant to the people, As a light to the Gentiles,

Isaiah 42:1-6

Upon this foundation, that Jesus Christ established His church

and revealed His words through his Apostles, that they should be

a light to the nations, offering salvation to the lost. On this

basis is the New Testament Canon revealed.

Before the establishment of the New Testament Canon,

the Old Testament was the Bible of the early church. Before

Jesus was crucified, he promised the coming of the Holy Spirit

who would help the Apostles remember the words spoken to them.

Here Jesus established the “Inspirational” aspect of the New

Covenant.

New Testament Inspiration

The

Holy Spirit inspires the New Testament like Old Testament; the

Holy Spirit is the source of the words contained in the pages of

the New Testament. Jesus when he was with His disciples

promised them they would be able to remember the words spoken,

through the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit would be the source of

their words.

25 "These things I have spoken to you while being present with

you. 26 "But the Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will

send in My name, He will teach you all things, and bring to your

remembrance all things that I said to you.John 14:25-26

Likewise, in the epistles and the rest of the New

Testament, the Holy Spirit is the source of the words, and not

human wisdom. Therefore, since God is the source of scripture,

it follows then; He has the ability to preserve His word for

coming generations.

10 But God has revealed them to us through His Spirit. For the

Spirit searches all things, yes, the deep things of God. 11 For

what man knows the things of a man except the spirit of the man

which is in him? Even so no one knows the things of God except

the Spirit of God. 12 Now we have received, not the spirit of

the world, but the Spirit who is from God, that we might know

the things that have been freely given to us by God. 13 These

things we also speak, not in words which man's wisdom teaches

but which the Holy Spirit teaches, comparing spiritual things

with spiritual. I Cor 2:10-13

Through his disciples, Jesus would reveal the Gospel to the

nations, through the inspiration of the Holy Sprit; “Truth”

would be transmitted to the “written document”. These documents

then would be compiled into the “New Testament canon”. The

apostles and prophets are the vehicle, which Jesus choose to

transmit the Gospel to the nations.

having been built on the foundation of the apostles and

prophets, Jesus Christ Himself being the chief cornerstone, 21in

whom the whole building, being fitted together, grows into a

holy temple in the Lord, 22in whom you also are being built

together for a dwelling place of God in the Spirit.

Ephesians 2:20

Why a New Testament Canon?

As Christianity began to spread throughout the Gentile world,

there developed several important reasons to establish, which

written works were from apostolic sources and which were from

heretical sources.

1. The Books were Prophetic

The books revealed through the Apostles were prophetic in

nature, since Jesus promised through the Holy Spirit to

communicate His words to His church. Therefore it was important

to establish just what books had apostolic authority and which

did not.

(2 Peter 3:15-17, Col. 4:16, 2 Tim.

3:16).

2. The needs of the early church

As the church grew in Asia, Africa and Europe, it became

important to establish, which books originated from apostolic

authority . Since the churches used the writing of the apostles

to establish doctrine and teach, it was mandatory to

discriminate against books, which had dubious origins.

3. Growth of the heretical movements

Since Jesus Christ established His church on the foundation of

the Apostles and prophets, heretical groups attempted to use the

names of apostles to establish their own particular doctrines,

many contrary to the revealed scriptures of the Old Testament.

One Gnostic group in particular Marcionites, founded by

Marcion, rejected the Old Testament, declaring the God of the

Old Testament, the God of the Jews, was a lower level deity.

Maricon, expelled from the church in A.D. 144, attempted to

establish a rival church. In addition to rejecting the Old

Testament, Marcion also rejected of all the epistles except for

the Pauline epistles

and the Gospel of Luke. Polycarp saw Marcion as a real threat to

the early church, upon meeting him; he called him, “The

Firstborn of Satan”.

In addition to the Marcionites, other sects also developed, each

with their own agenda and leader. Among these were the

Judaisers,

the Gnostics, The Mandaens and the Manichaens.

In order to establish their credibility, they published works

that included apostles names. Many of the writings of the early

church fathers, such as Irenaeus (A.D. 120-200) and Justin

Martyr (A.D. 100-165) fought with these heretical groups by

exposing and refuting their doctrines.

The false works, which originated with many of these

groups (i.e. Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Judas),

caused confusion for many as Christianity spread in Europe, Asia

and Africa. Many of the new believers needed an authoritative

list of books to distinguish between fallacious and authentic

works.

4. Missionary movements

As Christianity spread into foreign lands, the need for

translations of scripture was required, and since there was no

“Bible” but individual New Testament books, there was a need to

establish what books had apostolic authority and which

did not. In the first half of the 2nd century, the

books of the Bible were translated into Syriac, Old Latin, in

the 3rd century into Coptic both the Sahidic

and Bohairic versions.

5. Persecutions of the church

Since the time of Nero, the Christian church faced periods of

persecution, with this persecution Christians were forced to

surrender their scriptures. Since many viewed the “Words” in

their possession as the Word of God, many would willingly face

death, rather then surrender their scriptures.

In the Christian persecutions during the reign of Decius (A.D.

249-51) and Diocletian (A.D. 302-305) Christian scriptures were

specifically targeted for destruction. Those who refused to

relinquish them faced Roman execution. Eusebius (A.D. 318)

records the words of the Diocletian edict,

It was the nineteenth year of the

reign of Diocletian, and the month Dystrus, or March, as the

Romans would call it, in which as the festival of the Saviour’s

Passion was coming on, an imperial letter was everywhere

promulgated, ordering the razing of the churches to the ground

and the destruction by fire of the scriptures, and proclaiming

that those who held high positions would lose all civil rights,

while those in households, if they persisted in their profession

of Christianity, would be deprived of their liberty. Such was

the first document against us. But not long afterwards we were

further visited with other letters, and in them the orders was

given that the presidents of the churches should all, in every

place, be first committed to prison, and then afterwards

compelled by every kind of device to sacrifice.

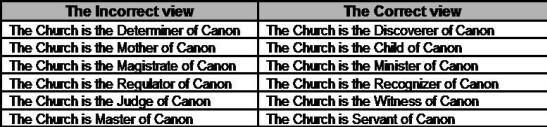

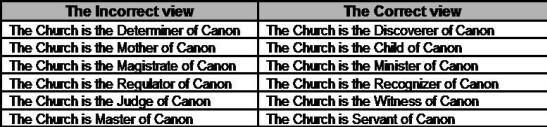

What qualifications were used to determine canon?

There needs to be a distinction

between discovery and selection of canon. The church did not

choose the canon, but discovered the canon. The

basis of New Testament canon is Jesus Christ and the revelation

of “inspired” scripture through the work of the Holy Spirit

(John 14:26). Jesus through His apostles established His

church, and through them revealed scripture. Therefore, the

basis of canon is apostolic authority. Therefore, the role in

the church in canon was to distinguish between apostolic works

built on the foundation of Jesus Christ, as opposed to

non-authoritative and false works, which claimed to be

inspired.

The Church was built on the foundation

of the disciples, who received their authority from Jesus

Christ. The canon is the written words of apostolic authority;

therefore, the church is the child of canon and not its mother.

These are important distinctions to understand when we examine

canon; the claim the church chose certain gospel over others is

false. The church, through councils and the witness of early

church fathers, recognized what books were authentic and which

were false.

These principles to

determine canon are based on the following principles.

1. Was the author an apostle or did it have apostolic authority?

For example, John Mark wrote the gospel of Mark, under the

authority of Peter. Luke was written under the authority of

Paul.

2. Does the document agree with the canon of truth?

Since the book is inspired, it will not contradict Old Testament

or authenticated New Testament canon.

3. Was the work accepted by the early church?

Could the work be verified in early church history? Was it

commented on by the early church fathers, or was it cited as

scripture? These were important questions in determining the

authentic nature of the books.

The Muratorian Canon

The principles of canon recognition are demonstrated in a Latin

manuscript found by Cardinal L.A. Muratori (1672-1750) in a

Ambrosian library in Milan Italy. The document was written in

the seventh to eight century, but was copied from an earlier

document dated to about A.D. 170, because it refers to the

episcopate of Pius I of Rome (died 157). He mentions only two

epistles of John, without describing them. The Apocalypse of

Peter is mentioned as a book which "some of us will not allow to

be read in church."

The manuscript is a fragment, therefore it starts with Luke

being the third book of the Gospels, Matthew and Mark would have

been the first and second. This list could have been a response

to Marcion’s canon list, since Marcion is specifically mentioned

at the end of the document.

. . at which nevertheless he was present, and so he placed [them

in his narrative]. (2) The third book of the Gospel is that

according to Luke. (3) Luke, the well-known physician, after the

ascension of Christ, (4-5) when Paul had taken with him as one

zealous for the law, (6) composed it in his own name, according

to [the general] belief. Yet he himself had not (7) seen the

Lord in the flesh; and therefore, as he was able to ascertain

events, (8) so indeed he begins to tell the story from the birth

of John. (9) The fourth of the Gospels is that of John, [one] of

the disciples. (10) To his fellow disciples and bishops, who had

been urging him [to write], (11) he said, 'Fast with me from

today to three days, and what (12) will be revealed to each one

(13) let us tell it to one another.' In the same night it was

revealed (14) to Andrew, [one] of the apostles, (15-16) that

John should write down all things in his own name while all of

them should review it. And so, though various (17) elements may

be taught in the individual books of the Gospels, (18)

nevertheless this makes no difference to the faith of believers,

since by the one sovereign Spirit all things (20) have been

declared in all [the Gospels]: concerning the (21) nativity,

concerning the passion, concerning the resurrection, (22)

concerning life with his disciples, (23) and concerning his

twofold coming; (24) the first in lowliness when he was

despised, which has taken place, (25) the second glorious in

royal power, (26) which is still in the future. What (27) marvel

is it then, if John so consistently (28) mentions these

particular points also in his Epistles, (29) saying about

himself, 'What we have seen with our eyes (30) and heard with

our ears and our hands (31) have handled, these things we have

written to you? (32) For in this way he professes [himself] to

be not only an eye-witness and hearer, (33) but also a writer of

all the marvelous deeds of the Lord, in their order. (34)

Moreover, the acts of all the apostles (35) were written in one

book. For 'most excellent Theophilus' Luke compiled (36) the

individual events that took place in his presence — (37) as he

plainly shows by omitting the martyrdom of Peter (38) as well as

the departure of Paul from the city [of Rome] (39) when he

journeyed to Spain. As for the Epistles of (40-1) Paul, they

themselves make clear to those desiring to understand, which

ones [they are], from what place, or for what reason they were

sent. (42) First of all, to the Corinthians, prohibiting their

heretical schisms; (43) next, to the Galatians, against

circumcision; (44-6) then to the Romans he wrote at length,

explaining the order (or, plan) of the Scriptures, and also that

Christ is their principle (or, main theme). It is necessary (47)

for us to discuss these one by one, since the blessed (48)

apostle Paul himself, following the example of his predecessor

(49-50) John, writes by name to only seven churches in the

following sequence: To the Corinthians (51) first, to the

Ephesians second, to the Philippians third, (52) to the

Colossians fourth, to the Galatians fifth, (53) to the

Thessalonians sixth, to the Romans (54-5) seventh. It is true

that he writes once more to the Corinthians and to the

Thessalonians for the sake of admonition, (56-7) yet it is

clearly recognizable that there is one Church spread throughout

the whole extent of the earth. For John also in the (58)

Apocalypse, though he writes to seven churches, (59-60)

nevertheless speaks to all. [Paul also wrote] out of affection

and love one to Philemon, one to Titus, and two to Timothy; and

these are held sacred (62-3) in the esteem of the Church

catholic for the regulation of ecclesiastical discipline. There

is current also [an epistle] to (64) the Laodiceans, [and]

another to the Alexandrians, [both] forged in Paul's (65) name

to [further] the heresy of Marcion, and several others (66)

which cannot be received into the catholic Church (67)— for it

is not fitting that gall be mixed with honey. (68) Moreover, the

epistle of Jude and two of the above-mentioned (or, bearing the

name of) John are counted (or, used) in the catholic [Church];

and [the book of] Wisdom, (70) written by the friends of

Solomon in his honour. (71) We receive only the apocalypses of

John and Peter, (72) though some of us are not willing that the

latter be read in church. (73) But Hermas wrote the Shepherd

(74) very recently, in our times, in the city of Rome, (75)

while bishop Pius, his brother, was occupying the [episcopal]

chair (76) of the church of the city of Rome. (77) And therefore

it ought indeed to be read; but (78) it cannot be read publicly

to the people in church either among (79) the Prophets, whose

number is complete, or among (80) the Apostles, for it is after

[their] time. (81) But we accept nothing whatever of Arsinous or

Valentinus or Miltiades, (82) who also composed (83) a new book

of psalms for Marcion, (84-5) together with Basilides, the Asian

founder of the Cataphrygians . .

The

Witness of the early church fathers

The Canon of the New Testament

I. Two Preliminary Considerations

The canon is the collection of 27 books, which the church

(generally) receives as its New Testament Scriptures. The

history of the canon is the history of the process by which

these books were brought together and their value as sacred

Scriptures officially recognized. That process was gradual,

furthered by definite needs, and, though unquestionably

continuous, is in its earlier stages difficult to trace. It is

always well in turning to the study of it to have in mind two

considerations which bear upon the earliest phases of the whole

movement. These are:

1. Early Christians Had the Old Testament

The early Christians had in their hands what was a Bible to

them, namely, the Old Testament Scriptures.

II. Three Stages of the Process

For convenience of arrangement and definiteness of impression

the whole process may be marked off in three stages:

1.

that from the time of the apostles until about 170

ad;

2.

that of the closing years of the 2nd century and the opening of

the 3rd (170-220 ad);

3.

that of the 3rd and 4th centuries. In the first we seek for the

evidences of the growth in appreciation of the peculiar value of

the New Testament writings; in the second we discover the clear,

full recognition of a large part of these writings as sacred and

authoritative; in the third the acceptance of the complete canon

in the East and in the West.

1. From the Apostles to 170 AD

(1) Clement of Rome; Ignarius; Polycarp

The first period extending

to 170 ad.—It does

not lie within the scope of this article to recount the origin

of the several books of the

New Testament. This belongs properly to New Testament

Introduction (which see). By the end of the 1st century all of

the books of the New Testament were in existence. They were, as

treasures of given churches, widely separated and honored as

containing the word of Jesus or the teaching of the apostles.

From the very first the authority of Jesus had full recognition

in all the Christian world. The whole work of the apostles was

in interpreting Him to the growing church. His sayings and His

life were in part for the illumination of the Old Testament;

wholly for the understanding of life and its issues. In every

assembly of Christians from the earliest days He was taught as

well as the Old Testament. In each church to which an epistle

was written that epistle was likewise read. Paul asked that his

letters be read in this way (1 Thess 5:27; Col 4:16). In this

attentive listening to the exposition of some event in the life

of Jesus or to the reading of the epistle of an apostle began

the “authorization” of the traditions concerning Jesus and the

apostolic writings. The widening of the area of the church and

the departure of the apostles from earth emphasized increasingly

the value of that which the writers of the New Testament left

behind them. Quite early the desire to have the benefit of all

possible instruction led to the interchange of Christian

writings.

Polycarp (110 ad ?)

writes to the Philippians, “I have received letters from you and

from Ignatius. You recommend me to send on yours to Syria; I

shall do so either personally or by some other means. In return

I send you the letter of Ignatius as well as others which I have

in my hands and for which you made request. I add them to the

present one; they will serve to edify your faith and

perseverance” (Epistle to Phil, XIII). This is an illustration

of what must have happened toward furthering a knowledge of the

writings of the apostles. Just when and to what extent

“collections” of our New Testament books began to be made it is

impossible to say, but it is fair to infer that a collection of

the Pauline epistles existed at the time Polycarp wrote to the

Phil and when Ignatius wrote his seven letters to the churches

of Asia Minor, i.e. about 115

ad. There is good reason to think also that the four

Gospels were brought together in some places as early as this. A

clear distinction, however, is to be kept in mind between

“collections” and such recognition as we imply in the word

“canonical.” The gathering of books was one of the steps

preliminary to this. Examination of the testimony to the New

Testament in this early time indicates also that it is given

with no intention of framing the canonicity of New Testament

books. In numerous instances only “echoes” of the thought of the

epistles appear; again quotations are incomplete; both showing

that Scripture words are used as the natural expression of

Christian thought. In the same way the Apostolic Fathers refer

to the teachings and deeds of Jesus.

Clement of Rome,

in 95 ad,

wrote a letter in the name of the Christians of Rome to those in

Corinth. In this letter he uses material found in Mt, Lk, giving

it a free rendering (see chapters 46 and 13); he has been much

influenced by the Epistle to the Hebrews (see chapters 9, 10,

17, 19, 36). He knows Romans, Corinthians, and there are found

echoes of 1 Timothy, Titus, 1 Peter and Ephesians.

The Epistles of

Ignatius

(115 ad)

have correspondences with our gospels in several places (Eph 5;

Rom 6; 7) and incorporate language from nearly all of the

Pauline epistles. The Epistle to Polycarp makes large use of

Phil, and besides this cites nine of the other Pauline epistles.

Ignatius quotes from Matthew, apparently from memory; also from

1 Peter and 1 John. In regard to all these three

writers—Clement, Polycarp, Ignatius—it is not enough to say that

they bring us reminiscences or quotations from this or that

book. Their thought is tinctured all through with New Testament

truth. As we move a little farther down the years we come to

“The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles” (circa 120

ad in its present form; see DIDACHE); the Epistle of

Barnabas (circa 130 ad)

and the Shepherd of Hermas (circa 130

ad). These exhibit the same phenomena as appear in the

writings of Clement, Ignatius and Polycarp as far as references

to the New Testament are concerned. Some books are quoted, and

the thought of the three writings echoes again and again the

teachings of the New Testament. They bear distinct witness to

the value of “the gospel” and the doctrine of the apostles, so

much so as to place these clearly above their own words. It is

in the Epistle of Barnabas that we first come upon the phrase

“it is written,” referring to a New Testament book (Matthew)

(see Epis., iv.14). In this deepening sense of value was

enfolded the feeling of authoritativeness, which slowly was to

find expression. It is well to add that what we have so far

discovered was true in widely separated parts of the Christian

world as e.g. Rome and Asia Minor.

(2) FORCES INCREASING VALUE OF WRITINGS

(A) Apologists, Justin Martyr

The literature of the period we are examining was not, however,

wholly of the kind of which we have been speaking. Two forces

were calling out other expressions of the singular value of the

writings of the apostles, whether gospels or epistles. These

were (a) the attention of the civil government in view of the

rapid growth of the Christian church and (b) heresy. The first

brought to the defense or commendation of Christianity the

Apologists, among whom were Justin Martyr, Aristides, Melito of

Sardis and Theophilus of Antioch. By far the most important of

these was Justin Martyr, and his work may be taken as

representative. He was born about 100 AD at Shechem, and died as

a martyr at Rome in 165 AD. His two Apologies and the Dialogue

with Trypho are the sources for the study of his testimony. He

speaks of the “Memoirs of the Apostles called Gospels” (Ap.,

i.66) which were read on Sunday interchangeably with the

prophets (i.67). Here emerges that equivalence in value of these

“Gospels” with the Old Testament Scriptures which may really

mark the beginning of canonization. That these Gospels were our

four Gospels as we now have them is yet a disputed question; but

the evidence is weighty that they were. (See Purves, Testimony

of Justin Martyr to Early Christianity, Lect V.) The fact that

Tatian, his pupil, made a harmony of the Gospels, i.e. of our

four Gospels, also bears upon our interpretation of Justin’s

“Memoirs.” (See Hemphill, The Diatessaron of Tatian.) The only

other New Testament book which Justin mentions is the

Apocalypse; but he appears to have known the Acts, six epistles

of Paul, Hebrew and 1 John, and echoes of still other epistles

are perceptible. When he speaks of the apostles it is after this

fashion: “By the power of God they proclaimed to every race of

men that they were sent by Christ to teach to all the Word of

God” (Ap., i.39). It is debatable, however, whether this refers

to more than the actual preaching of the apostles. The beginning

of the formation of the canon is in the position and authority

given to the Gospels.

(B) Gnostics, Marcion

While the Apologists were busy commending or defending

Christianity, heresy in the form of Gnosticism was also

compelling attention to the matter of the writings of the

apostles. From the beginning Gnostic teachers claimed that Jesus

had favored chosen ones of His apostles with a body of esoteric

truth which had been handed down by secret tradition. This the

church denied, and in the controversy that went on through years

the question of what were authoritative writings became more and

more pronounced. Basilides e.g., who taught in Alexandria during

the reign of Hadrian (AD 117-38), had for his secret authority

the secret tradition of the apostle Matthias and of Glaucias, an

alleged interpreter of Peter, but he bears witness to Matthew,

Luke, John, Romans, 1 Corinthians, Ephesians, and Colossians in

the effort to recommend his doctrines, and, what is more, gives

them the value of Scripture in order to support more securely

his teachings. (See Philosophoumena of Hippolytus, VII, 17).

Valentinus, tracing his authority through Theodas to Paul, makes

the same general use of New Testament books, and Tertullian

tells us that he appeared to use the whole New Testament as then

known.

The most noted of the Gnostics was Marcion, a native of Pontus.

He went to Rome (circa 140 AD), there broke with the church and

became a dangerous heretic. In support of his peculiar views, he

formed a canon of his own which consisted of Luke’s Gospel and

ten of the Pauline epistles. He rejected the Pastoral Epistles,

Hebrews, Matthew, Mark, John, the Acts, the Catholic epistles

and the Apocalypse, and made a recension of both the gospel of

Luke and the Pauline epistles which he accepted. His importance,

for us, however, is in the fact that he gives us the first clear

evidence of the canonization of the Pauline epistles. Such use

of the Scriptures inevitably called forth both criticism and a

clearer marking off of those books which were to be used in the

churches opposed to heresy, and so “in the struggle with

Gnosticism the canon was made.” We are Thus brought to the end

of the first period in which we have marked the collection of

New Testament books in greater or smaller compass, the

increasing valuation of them as depositions of the truth of

Jesus and His apostles, and finally the movement toward the

claim of their authoritativeness as over against perverted

teaching. No sharp line as to a given year can be drawn between

the first stage of the process and the second. Forces working in

the first go on into the second, but results are accomplished in

the second which give it its right to separate consideration.

2. From 170 AD to 220 Ad

The period from 170 AD to 220 AD.—This is the age of a

voluminous theological literature busy with the great issues of

church canon and creed. It is the period of the great names of

Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, and Tertullian, representing

respectively Asia Minor, Egypt and North Africa. In passing into

it we come into the clear light of Christian history. There is

no longer any question as to a New Testament canon; the only

difference of judgment is as to its extent. What has been slowly

but surely shaping itself in the consciousness of the church now

comes to clear expression.

(1) IRENAEUS

That expression we may study in Irenaeus as representative of

the period. He was born in Asia Minor, lived and taught in Rome

and became afterward bishop of Lyons. He had, therefore, a wide

acquaintance with the churches, and was peculiarly competent to

speak concerning the general judgment of the Christian world. As

a pupil of Polycarp, who was a disciple of John, he is connected

with the apostles themselves. An earnest defender of the truth,

he makes the New Testament in great part his authority, and

often appeals to it. The four Gospels, the Acts, the epistles of

Paul, several of the Catholic epistles and the Apocalypse are to

him Scripture in the fullest sense. They are genuine and

authoritative, as much so as the Old Testament ever was. He

dwells upon the fact that there are four gospels, the very

number being prefigured in the four winds and the four quarters

of the earth. Every attempt to increase or diminish the number

is heresy. Tertullian takes virtually the same position (Adv.

Marc., iv. 2), while Clement of Alexandria quotes all four

gospels as “Scripture.” By the end of the 2nd century the canon

of the gospels was settled. The same is true also of the Pauline

epistles. Irenaeus makes more than two hundred citations from

Paul, and looks upon his epistles as Scripture (Adv. Haer.,

iii.12, 12). Indeed, at this time it may be said that the new

canon was known under the designation “The Gospel and the

Apostles” in contradistinction to the old as “the Law and the

Prophets.” The title “New Testament” appears to have been first

used by an unknown writer against Montanism (circa 193 AD). It

occurs frequently after this in Origen and later writers. In

considering all this testimony two facts should have emphasis:

(1) its wide extent: Clement and Irenaeus represent parts of

Christendom which are widely separated; (2) The relation of

these men to those who have gone before them. Their lives

together with those before them spanned nearly the whole time

from the apostles. They but voiced the judgment which silently,

gradually had been selecting the “Scripture” which they freely

and fully acknowledged and to which they made appeal.

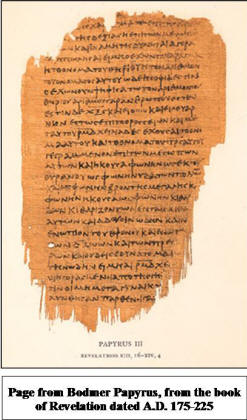

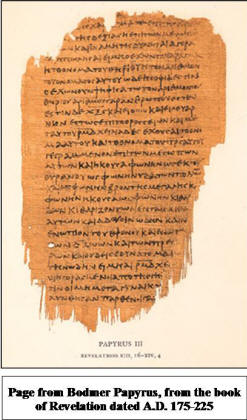

(2) THE MURATORIAN FRAGMENT

Just here we come upon the Muratorian Fragment, so called

because discovered in 1740 by the librarian of Milan, Muratori.

It dates from some time near the end of the 2nd century, is of

vital interest in the study of the history of the canon, since

it gives us a list of New Testament books and is concerned with

the question of the canon itself. The document comes from Rome,

and Lightfoot assigns it to Hippolytus. Its list contains the

Gospels (the first line of the fragment is incomplete, beginning

with Mark, but Matthew is clearly implied), the Acts, the

Pauline epistles, the Apocalypse, 1 and 2 John (perhaps by

implication the third) and Jude. It does not mention Hebrew, 1

and 2 Peter, James. In this list we have virtually the real

position of the canon at the close of the 2nd century. Complete

unanimity had not been attained in reference to all the books

which are now between the covers of our New Testament. Seven

books had not yet found a secure place beside the gospel and

Paul in all parts of the church. The Palestinian and Syrian

churches for a long time rejected the Apocalypse, while some of

the Catholic epistles were in Egypt considered doubtful. The

history of the final acceptance of these belongs to the third

period.

3. 3rd and 4th Centuries

(1) ORIGEN

The period included by the 3rd and 4th centuries—It

has been said that “the question of the canon did not make much

progress in the course of the 3rd century” (Reuss, History of

the Canon of Holy Scripture, 125). We have the testimony of

a few notable teachers mostly from one center, Alexandria. Their

consideration of the question of the disputed book serves just

here one purpose. By far the most distinguished name of the 3rd

century is Origen. He was born in Alexandria about 185

ad, and before he was seventeen became an instructor in

the school for catechumens. In 203 he was appointed bishop,

experienced various fortunes, and died in 254. His fame rests

upon his ability as an exegete, though he worked laboriously and

successfully in other fields. His testimony is of high value,

not simply because of his own studies, but also because of his

wide knowledge of what was thought in other Christian centers in

the world of his time. Space permits us only to give in summary

form his conclusions, especially in regard to the books still in

doubt. The Gospels, the Pauline epistles, the Acts, he accepts

without question. He discusses at some length the authorship of

He, believes that “God alone knows who wrote it,” and accepts it

as Scripture. His testimony to the Apocalypse is given in the

sentence, “Therefore John the son of Zebedee says in the

Revelation.” He also gives sure witness to Jude, but wavers in

regard to James, 2 Peter, 2 John, and 3 John.

(2) Dionysius

Another noted name of this century is Dionysius of Alexandria,

a pupil of Origen (died 265). His most interesting discussion is

regarding the Apocalypse, which he attributes to an unknown

John, but he does not dispute its inspiration. It is a singular

fact that the western church accepted this book from the first,

while its position in the East was variable. Conversely the

Epistle to the He was more insecure in the West than in the

East. In regard to the Catholic epistles Dionysius supports

James, 2 John, and 3 John, but not 2 Peter or Jude.

(3) Cyprian

In the West the name of Cyprian, bishop of Carthage

(248-58 ad), was most influential. He was much engaged in

controversy, but a man of great personal force. The Apocalypse

he highly honored, but he was silent about the Epistle to the

Hebrews. He refers to only two of the Catholic epistles, 1 Peter

and 1 John.

These testimonies confirm what was said above, namely, that the

end of the 3rd century leaves the question of the full canon

about where it was at the beginning. 1 Peter and 1 John seem to

have been everywhere known and accepted. In the West the five

Catholic epistles gained recognition more slowly than in the

East.

(4) Eusebius

In the early part of the 4th century Eusebius (270-340 ad), bishop of Caesarea before 315, sets before us in his

Church History (III, chapters iii-xxv) his estimate of the

canon in his time. He does not of course use the word canon, but

he “conducts an historical inquiry into the belief and practice

of earlier generations.” He lived through the last great

persecution in the early part of the 4th century, when not only

places of worship were razed to the ground, but also the sacred

Scriptures were in the public market-places consigned to the

flames (Historia Ecclesiastica, VIII, 2). It was,

therefore, no idle question what book a loyal Christian must

stand for as his Scripture. The question of the canon had an

earnest, practical significance. Despite some obscurity and

apparent contradictions, his classification of the New Testament

books was as follows: (1) The acknowledged books. His criteria

for each of these was authenticity and apostolicity and he

placed in this list the Gospels, Acts, and Paul’s epistles,

including He. (2) The disputed books, i.e. those which had

obtained only partial recognition, to which he assigned Jas,

Jude, 2 Pet and 2 Jn. About the Apocalypse also he was not sure.

In this testimony there is not much advance over that of the 3rd

century. It is virtually the canon of Origen. All this makes

evident the fact that as yet no official decision nor uniformity

of usage in the church gave a completed canon. The time,

however, was drawing on when various forces at work were to

bring much nearer this unanimity and enlarge the list of

acknowledged books. In the second half of the 4th century

repeated efforts were made to put an end to uncertainty.

(5) Athanasius

Athanasius

in one of his pastoral letters in connection with the publishing

of the ecclesiastical calendar gives a list of the books

comprising Scripture, and in the New Testament portion are

included all the 27 books which we now recognize. “These are the

wells of salvation,” he writes, “so that he who thirsts may be

satisfied with the sayings in these. Let no one add to these.

Let nothing be taken away.” Gregory of Nazianzen (died 390

ad) also published a list omitting Revelation, as did

Cyril of Jerusalem (died 386), and quite at the end of the

century (4th) Isidore of Pelusium speaks of the “canon of truth,

the Divine Scriptures.” For a considerable time the Apocalypse

was not accepted in the Palestinian or Syrian churches.

Athanasius helped toward its acceptance in the church of

Alexandria. Some differences of opinion, however, continued. The

Syrian church did not accept all of the Catholic epistles until

much later.

(6) Council of Carthage, Jerome; Augustine

The Council of Carthage in 397,

in connection with its decree “that aside from the canonical

Scriptures nothing is to be read in church under the name of

Divine Scriptures,” gives a list of the books of the New

Testament. After this fashion there was an endeavor to secure

unanimity, while at the same time differences of judgment and

practice continued. The books which had varied treatment through

these early centuries were He, the Apocalypse and the five minor

Catholic epistles. The advance of Christianity under Constantine

had much to do with the reception of the whole group of books in

the East. The task which the emperor gave to Eusebius to prepare

“fifty copies of the Divine Scriptures” established a standard

which in time gave recognition to all doubtful books. In the

West, Jerome and Augustine were the controlling factors in its

settlement of the canon. The publication of the Vulgate

(Jerome’s Latin Bible, 390-405

ad) virtually

determined the matter.

In conclusion let it be noted how much the human element was

involved in the whole process of forming our New Testament. No

one would wish to dispute a providential overruling of it all.

Also it is well to bear in mind that all the books have not the

same clear title to their places in the canon as far as the

history of their attestation is concerned. Clear and full and

unanimous, however, has been the judgment from the beginning

upon the Gospels, the Acts, the Pauline epistles, 1 Peter and 1

John.

LiteratureReuss,

History of the Canon of Holy Scriptures; E. C. Moore,

The New Testament in the Christian Church; Gregory, Canon

and Text of the New Testament; Introductions to New

Testament of Jülicher, Weiss, Reuss; Zahn, Geschichte des

Neutest. Kanons; Harnack, Das New Testament um das Jahr

200; Chronologie der altchristlichen Literatur;

Westcott, The Canon of the New Testament; Zahn,

Forschungen zur Gesch. des neutest. Kanons.J. S. Riggs

|

For

Christians today, their Bible has an Old and New Testament; both

testaments are a collection of books revealed over time. The

Old Testament was revealed over a thousand year period, 1450

B.C. to 425 B.C.; the New Testament is separated from the New

Testament by a 450-year period known as the Inter-testimonial

period. The New Testament, unlike the Old was revealed over

a much shorter time, a sixty-year period, from A.D. 33 to 100.

For

Christians today, their Bible has an Old and New Testament; both

testaments are a collection of books revealed over time. The

Old Testament was revealed over a thousand year period, 1450

B.C. to 425 B.C.; the New Testament is separated from the New

Testament by a 450-year period known as the Inter-testimonial

period. The New Testament, unlike the Old was revealed over

a much shorter time, a sixty-year period, from A.D. 33 to 100.