|

The Quran: The Scripture of Islam

John Gilchrist

Chapter One:

The Composition and

Character of the Qurčan

1. Muslim Reverence for the Quran

The Divine Excellence of the Islamic Scripture

The quran Qurčan is the holy scripture of the Muslim

peoples of the world. It is, in their eyes, the divine

authentication of the faith they boldly profess.

Although Muhammad, the Prophet of Islam, is revered as

the greatest of all Allah's servants, he is regarded as

only a human messenger who lived and died like any

mortal. The cities of Mecca and Medina are likewise

regarded as possessing a special sanctity but, as with

all other tangible things in the Islamic world, they are

nothing more than material parts of the created order.

The quran Qurčan, however, came from above and is the

kalam of Allah, the divine word or speech expressing a

sifa, an actual quality of his own personality and

being. Even though the text of the quran Qurčan in book

form may well have been compiled from earthly materials,

the actual text represented is nonetheless no less than

a visual record of a divine communication sent down from

heaven itself.

During the early centuries of Islam a debate arose in

the Muslim world as to whether the quran Qurčan itself,

though the speech of Allah, was nevertheless created at

a point in time. A group of free-thinkers had arisen who

became known as the mutazila Mu tazila with their

principal base in Baghdad, the city where the Abbasid

rule over the Muslim world had been established. They

did not doubt that the quran Qurčan was Allah's speech

but, believing that the human intellect was the ultimate

source of all knowledge, they taught that the quran

Qurčan was only a part of the created order which,

having been brought into existence at an undetermined

time, therefore had a beginning and could not be said to

be divine itself. The orthodox Muslims, however, argued

strongly in opposition to this view. They declared that,

being the Word of Allah, it could not be separated from

him and must have co-existed with him, uncreated,

through all eternity. It had, from this divine source,

simply been sent down and revealed to Muhammad at the

most appropriate point in human history. Their view

prevailed and ever since the quran Qurčan has been held

to be uncreated. The quran Qurčan itself teaches that

its written form on earth is merely a reflection of an

exact original inscribed in heaven:

Assuredly this is a Majestic quran Qurčan (inscribed)

in a Preserved Tablet. Surah 85. 21-22.

Most English translations of the quran Qurčan carry

the title "The Holy quran Qurčan" and Christians may be

inclined to think that it is the Muslim equivalent of

the Holy Bible. To the extent that each book

respectively is believed to be a form of divinely

inspired Scripture and is the written source of all

knowledge about God's revealed truth, the books are very

similar. There is a fundamental difference, however,

which has to be fully recognised if Muslim reverence for

the quran Qurčan is to be understood. The Bible is a

record of the writings of numerous prophets of God and

the apostles of Christ (in the Old and New Testaments

respectively) who wrote under the inspiration of the

Spirit of God and is therefore the preserved Word of God

for mankind. God himself often speaks directly through

these writings and his messages are recorded in numerous

books, yet the form of each always takes that of a human

author writing under the inerrant guidance of the Holy

Spirit. God's actual words are included as quotations of

prior direct communications to the relevant hearers.

Allah himself, however, is believed to be the actual

author of the quran Qurčan. Here, too, one finds

numerous passages where men, angels, prophets and even

Satan himself speak, yet this time it is their words

which are the quotations. Allah is always the speaker

and what was recorded by Muhammad at any time as the

quran Qurčan came to him was nothing less than a

revelation from Allah himself. Over a period of

twenty-three years it came to him through the medium of

the angel Jibril, said to be the angel Gabriel (Surah

2.97), after having been sent down to the first heaven

during the month of Ramadan. Allah speaks directly to

the Prophet in the quran Qurčan in these words:

And in Truth We have sent it down, and in Truth it

has descended, and We have sent you to be nothing more

than a Proclaimer and Warner. And it is a quran Qurčan

which We have (sent) piecemeal so that you may recite it

to men in stages, and We have sent it down accordingly.

Surah 17. 105-106.

The quran Qurčan itself often appeals to its own

uniqueness, stating that it contains a "beautiful

message" (Surah 39.23) and that no falsehood can come

near it (Surah 41.42). It further states that it has

been sent down in "pure Arabic" (Surah 16.103) and

challenges its detractors to attempt to produce the like

of it:

And if you are in doubt about what We have sent down

upon Our servant then produce a surah like it, and call

your witnesses besides Allah if you are truthful. Surah

2.23

A "surah" is a passage of writing and each chapter of

the quran Qurčan is thus called. The book literally

commands reverence and the utmost respect from its

adherents and Muslims accordingly are very devoted to

it. They are told to seek Allah's protection from the

Evil One before reciting it (Surah 16.98) and, in words

very similar to those set out in this text, they say

auuthuu A uuthuu billaahi minash-shaytaanir-rajiim-"I

seek refuge in Allah from Satan the stoned". They follow

this by reading the bismillah, the heading of every

chapter of the quran Qurčan excepting the ninth surah,

which reads Bismillaahir-Rahmaanir-Rahiim-"In the Name

of Allah, the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful".

Only then is the quran Qurčan itself recited. It is

furthermore essential that it be recited properly and

Muslims go to great lengths to learn by heart passages

to perfection.

To impress all the more upon Muslims that the book is

Allah's own Word the quran Qurčan constantly commands

them to bring him to remembrance as they recite it so

that its reading may not become an end in itself. Unlike

the Bible, which Christians generally read in their own

languages to discover its message, the Muslim finds

merit just in reciting the quran Qurčan in its original

Arabic even if he does not fully understand what he is

reading. It is in this recitation that the Muslim is

required to fix his mind on Allah:

And when the quran Qurčan is recited, listen

attentively and be silent so that you may find mercy.

And bring the Remembrance of your Lord into your soul

humbly and reverently, not loud of voice, in the morning

and evening. And do not be among the heedless. Surah 7.

204-205.

They are also commanded to recite it slowly (Surah

73.4) so that a spirit of reverent awareness of Allah

himself may always prevail. The "Remembrance" of Allah

is known popularly in Islam as al-Dhikr and the Sufi

Muslims of the world (the mystics of Islam) have special

ceremonies for this express purpose. The quran Qurčan

itself is called al-Dhikr on eight occasions (eg. Surah

15.6, 15.9) indicating its function as a summons to the

recollection of Allah and his glory.

The Historic Sanctity of the Written Text

During Muhammad's own lifetime portions of the quran

Qurčan were committed to writing on various materials

and not long after his death the whole book was codified

into a single text. Over the centuries copies were

transcribed and in recent times the quran Qurčan has

been printed and sold throughout the world. As can be

expected written quran Qurčans are very highly respected

and old handwritten manuscripts are especially prized.

Most ancient manuscripts of the quran Qurčan were

carefully written, not only to avoid mistakes, but to

reproduce the text as impressively as possible. The

early script known as kufi was soon adapted into a form

of art and calligraphy and transcribers meticulously

preserved the text by writing it out as perfectly as

they could. If just a stroke or letter was not

faultlessly reproduced they would scrap the page and

start again.

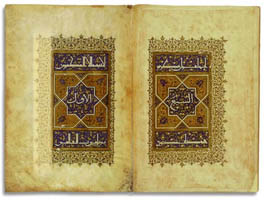

In later centuries such manuscripts became decorated

with colourful headings and the first chapter of the

quran Qurčan, known as Suratul-Fatihah ("The Opening

Chapter"), together with the first few verses of the

next chapter was beautifully outlined in oriental style.

Gold-leaf margins and outlines were mixed with dark blue

backgrounds and other colourful styles and motifs (often

floral) to give an appearance of grandeur to the text.

Such a decoration became known as an unwan and virtually

all the old handwritten texts have them. Other chapter

headings were also decorated in colourful style with

gold-leaf always a choice addition to give class to

their appearance while floral and arabesque medallions

alongside the text added to the charm of the manuscript.

The script changed as well after the first few

centuries and the naskhi script became the most popular

and most of the surviving copies of old quran Qurčan

manuscripts employed it. The similar thuluth script was

used at times and to this day a cursive script known as

maghribi ("western") is still used in countries such as

Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. Virtually all printed

quran Qurčans employ the naskhi script. The oldest

surviving passages of handwritten texts dating to the

second century of Islam are inscribed in a slanted text

known as al mail al-ma il. More will be said on this

subject in the last section of this book.

As a result of the conviction that the quran Qurčan

is the uncreated kalam of Allah, certain scruples

surround handwritten or printed copies of its text. It

is a belief of the strictly orthodox that the quran

Qurčan should never be touched or opened by anyone other

than a true Muslim and certain ablutions should be

observed before this is done. The quran Qurčan itself

says "None shall touch it but those who are clean"

(Surah 56.79) and a tradition emphasises the need for a

proper ablution:

`Abd Allah b. Abu Bakr b. Hazm reported: The book

written by the Apostle of Allah (may peace be upon him)

for `Amr b. Hazm contained this also that no man should

touch the quran Qurčan without ablution. (Muwatta Imam

Malik, p.94).

It is also customary to have a small ledge as close

to the roof as possible upon which the quran Qurčan is

to be placed when it is not being read as it should

obtain the highest place in the home. Muslims will also

not leave a quran Qurčan on a chair, seat or bed as this

is believed to be common property where people have sat

or lain and unsuitable for such a book. For the same

reason a quran Qurčan should never be placed on the

ground where people have walked. Special wooden quran

Qurčan stands are provided in mosques upon which the

book can be placed while the reader is sitting on the

ground. The book should be kissed before it is opened

and, once read, it should be closed as a tradition

prevails among Muslims that Satan will come and read an

open quran Qurčan if no one else is reading it.

In closing it should be added that the grammatical

form of the quran Qurčan has become the standard by

which all good Arabic grammar is tested. It is presumed

beforehand that the text is unimpeachable and its style

likewise has become the norm by which all other Arabic

writings can be evaluated. Any deviation from its method

is regarded as a defect. Even in the realm of literary

criticism this principle holds sway. Many Western

scholars of Arabic history have believed that some of

the Arabic literature quoted in al-Baqillani's ijaz

I jaz quran al-Qurčan is of a far superior quality to

the monotonous tone of the quran Qurčan, yet these works

perforce have to be regarded as subordinate to it simply

because the quran Qurčan is presumed to be the standard

by which all other poetry and literature must be

evaluated (and, accordingly, deemed inferior!). If

anyone was to attempt to "produce a surah like it" he

could be sure by these very principles of comparison

that he would have no prospect of success.

2. The Outline, Nature and Form of the Book

quranic

The Basic Structure of the Qurčanic Text

The quran Qurčan is almost the length of the New

Testament though its structure and form is very

different to it. It is comprised of one hundred and

fourteen surahs which are of unequal length and are not

compiled in any sort of chronological order.

The longest surahs occur first and, as one progresses

through the quran Qurčan, the chapters become shorter

and shorter so that, whereas the second surah has two

hundred and eighty-six verses, the last ten are made up

of only a few lines each.

Each surah has a title usually taken from a

significant word or name usually at the beginning of the

text. Some introduce the major theme of the surah, for

example the twelfth chapter which is known as

Suratu-Yusuf, "Chapter of Joseph", because he is its

central theme. It is interesting to discover that,

although other Biblical prophets are mentioned

throughout the quran Qurčan at various points, Joseph is

not referred to anywhere else in the book. It appears

that Muhammad only heard of him and the story of his

life during his later years as this surah is one of the

last said to have been revealed to him. Yet it is

obvious from the following verse taken from its

introduction that he was very moved by it:

We relate to you a most beautiful story, in that we

reveal to you this (part of the) quran Qurčan, though

before it you were among those ignorant of it. Surah

12.3

The nineteenth chapter is titled Suratu-Maryam, the

"Chapter of Mary", because the mother of Jesus is its

central theme. Nonetheless the quran Qurčan also has

another well defined division, this time into thirty

sections of virtually equal length, which Muslims also

describe as "chapters" or portions but which are known

by a different name. Each one is called a Juz' or, in

the popular Persian terminology, a Siparah (from si -

"thirty" - and parah - "portions"). There is no

correlation between these and the surahs of the quran

Qurčan and their identification in a written quran

Qurčan is not so obvious. In some they are marked by a

medallion alongside the text, in many printed quran

Qurčans by an accentuation or decoration of the first

verse of each successive passage. The purpose of this

division is to enable Muslims to recite the quran Qurčan

each night during the thirty nights of the holy month of

Ramadan, the month in which all Muslims are compelled to

fast from sunrise to sunset.

At the beginning of twenty-nine of the surahs of the

quran Qurčan, just after the bismillah, are certain

Arabic letters not forming a word. No one knows what

they mean and a number of interesting interpretations

and suggestions have been made to unravel their purpose.

Some learned Muslims have claimed that they have a

profound meaning known only to Muhammad himself but

nothing can be said of them with any certainty. At least

six surahs begin with the letters alif, lam, mim.

Nonetheless to Muslims generally the meaning of these

letters is not important as the recitation of the quran

Qurčan is regarded as just as vital as applying its

teachings. The very word al quran Al-Qur'an means "The

Recitation" and the practice is so seriously regarded by

Muslims that they will go to great lengths just to learn

its correct pronunciation, a pursuit now developed into

a science and known as ilmut tajwid ilmut-tajwid, the

"knowledge of pronunciation". The actual recitation of

the quran Qurčan is known as tilawah and it appears from

the following tradition that even Muhammad was concerned

to be scrupulous in this matter:

Gabriel used to recite the quran Qurčan before our

Prophet, may Allah bless him, once every year in

Ramadan. In the year in which he breathed his last he

recited it twice before him. Muhammad said: I hope our

style of reading conforms to the last recitation by

Gabriel.

(Ibn sad Sa d, Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabir, Vol.2,

p.243).

Each surah of the quran Qurčan is also broken up into

brief sections known as rukuah ruku ah as Muslims deem

it commendable to make a bow in reverence, a ruku ruku ,

at the end of the recitation of each of these sections.

They are designated in the quran Qurčan by the Arabic

letter ain ain in the margin and are accompanied by the

section number and number of verses in each case. Often

these designations are also embellished with floral

rosettes or other forms of medallion.

The quran Qurčan has a number of names for itself. It

is called quranul majid Qurčanul-Majid, "a Glorious

quran Qurčan" in Surah 85.21 and is elsewhere described

as quranul karim Qurčanul-Karim, "a Noble quran Qurčan"

(Surah 56.77). In Surah 36.2 its title is al quranul

hakim al-Qur'anul-Hakim, "the Wise quran Qurčan" and

many modern printed quran Qurčans employ one or more of

these names in the title-page of the book. One such

quran Qurčan is titled quran Qurčan Karim wa Furqan

Adhim, "a Noble quran Qurčan and an Exalted Criterion".

The title al-Furqan itself is applied to the quran

Qurčan in Surah 25.1 and it implies that the holy book

is the "criterion" by which all truth can be

distinguished from falsehood and all right from wrong.

Unique Features in the Form and Style of the Book

The quran Qurčan is very different to the Bible in

that it was compiled through the mediation of only one

man over a period of twenty-three years until the day of

his death. It was only this event that sealed the length

and content of the book. As long as Muhammad remained

alive there was always a possibility that fresh material

could be added.

The book itself, as stated already, has no

chronological sequence. While it covers large parts of

Biblical history and freely acknowledges the former

prophets, it not only does not attempt to give any kind

of historical sequence to the events it records but it

also offers no locality or time in history when they

occurred. The only place mentioned by name in the quran

Qurčan is Mecca (Bakkah in the text of Surah 3.96) and

no dating whatsoever of any event is recorded. Unless

the reader of the quran Qurčan is familiar with these

from another source-the Bible in particular - he has no

hope of being able to compose a picture of prophetic

history.

The story of Jonah is not dated in the Bible but the

short narrative in the book of the same name leaves no

doubt as to exactly what took place and where he went.

The story is patchily reproduced in the quran Qurčan in

Surah 37. 139-148 and is lacking vital details. The

cities of Tarshish and Nineveh are omitted and no

mention is made of the storm which led to him being

thrown overboard into the sea, though his condemnation

by lots is recorded. The reader is, it appears, presumed

to know the story in its basic details. On the positive

side the quran Qurčan can be viewed as a Scripture

intended for edification which need not concern itself

with factual or chronological details long receded into

history. It does not seem to be interested in the events

it records from a historical perspective nor in

localities or personalities as such. These are secondary

and incidental to the real theme-the relevance of

Allah's dealings and experiences with men in former

times as examples for the present and the future. It

engages with incidents and refers to them only to suit

its own purposes.

Nonetheless there are times when the reader cannot

help getting the impression that details may be lacking

as a result of insufficient information being available

to the book's author. The quran Qurčan records a story

similar to Nathan's parable to David in 2 Samuel 12. 1-6

but it states that the incident was a real one where two

disputants actually came into his presence, the one

complaining that the other had taken his only ewe when

he already had ninety-nine of his own (Surah 38. 22-23).

When David angrily pronounced judgment against the

second litigant, the text says he suddenly realised that

he had personally been tried through it and fell down

asking forgiveness. No indication is given as to what he

had done wrong nor how the story related to his own

offence. Surah 38.25 adds that Allah then forgave him

for "this", not hinting as to what it was. Again,

without recourse to the comprehensive narrative of the

whole event in the Bible, the reader cannot hope to

discover what the quran Qurčan is talking about.

A good example of the somewhat haphazard structure of

the quran Qurčan is found in the passage which follows

the story of Jonah in Surah 37. The next verses (Surah

37. 149-157) contain an admonition about the pagan Arab

belief that certain idols were the daughters of Allah.

How could he only have daughters while they had sons (in

the light of the Arab belief that sons were a blessing

but daughters a misfortune)? The passage has no

connection whatsoever with what went before it.

Virtually the whole of the quran Qurčan is compiled in

this way.

This last-mentioned passage, however, is symbolic of

one of the unique features of the quran Qurčan. The book

constantly employs argument and reasoning to convince

its hearers of its message. As an appeal to the pagan

Arabs not to persist in idolatry the quran Qurčan argues

strongly from the evidences around them of an obvious

single source of all creation (similar to Paul's

reasoning in Romans 1.20):

Who has made the earth your couch, and the heavens

your canopy; and sent down rain from heaven, and brought

forth fruits for your provision? So do not knowingly set

up rivals to Allah. Surah 2.22

Similar disputational reasoning is used in Surah 6.32

where it is argued that the amusements and frivolity of

life of this world are obviously temporal and that a

much wiser occupation would be the pursuit of a

permanent home in the hereafter. Will they not then

understand? Likewise, in a few verses further on, the

pagans are asked who they would appeal to if Allah's

wrath or the final Hour were suddenly to come upon them

(Surah 6.40). Against the Christians the quran Qurčan

charges "How can Allah have a son when he has no wife?"

(Surah 6.101). It is ironic that Mary asks a similar

question, not objectionably but by way of enquiry, in

Surah 3.47 where she too asks how she could have a son

when she had no husband? In the next verse the quran

Qurčan declares that Allah can do as he wills and that

he only has to speak the word kun ("Be!") and fayakun

("it comes to be"). Surah 19.21 adds that such things

are easy for Allah. By the same reasoning the quran

Qurčan should be able to answer its own question in

Surah 6.101. Nonetheless these passages are typical of

many where the spirit of argumentative reasoning is

employed in the book.

In the earlier passages of the quran Qurčan which

concentrate on sharp, prophetic pronouncements a

catching rhythmical prose is used with poetic effect.

This saj saj style tends to fall away in the later

passages which deal with practical issues at greater

length but its use is one of the features of the quran

Qurčan. (It is important to remember that the earliest

portions of the quran Qurčan are generally found in the

surahs at the end of the book while the later portions

paradoxically appear at the beginning).

Although the quran Qurčan is said to be an eternal

Scripture and that the Prophet of Islam was commissioned

solely to communicate its contents without any

involvement in its compilation, it interacts with him

and addresses him personally on numerous occasions. He

is commanded to "Say" (qul) that he is only a man like

all others but that an inspiration has come upon him

(Surah 18.110); he is bidden to invite people to his

Lord's way with wisdom and beautiful preaching and to

argue in gracious terms (Surah 16.125); he is to strive

against unbelievers and hypocrites and to be firm with

them (Surah 66.9) and is admonished for frowning and

turning away from a blind man who might have profited

from his teaching, especially as he came to him in

earnest sincerity (Surah 80. 1-10).

The quran Qurčan is in many ways a unique book in its

outline, style and form. It can take time for a

non-Muslim to become acquainted with these features but

the exercise is essential if it is to be understood.

3. Important Surahs, Cliches and Passages

The Opening Chapter and Other Major Surahs

Some of the chapters and passages of the quran Qurčan

are regarded as having a special sanctity and their

recital is believed to be imperative and very

meritorious. The most important of these is the

Suratul-Fatihah which is unusual in its placing as the

opening chapter of the book. It has only seven verses,

unlike the other early surahs which are the longest in

its text. It is set out as a prayer to be addressed to

Allah:

In the name of Allah, the Compassionate, the

Merciful. Praise be to Allah, the Lord of the worlds;

the Compassionate, the Merciful, Master of the Day of

Judgment. You alone we worship and from You alone we

seek help. Lead us into the Straight Path; the path of

those whom you have favoured, not those with whom you

are angry, or go astray. Surah 1. 1-7.

This is one of the few passages in the quran Qurčan

where Allah is not speaking directly but where the text

is put into the mouth of Muslims who worship him. Every

time Muslims pray or visit the mosque this prayer is

offered up to Allah in its Arabic original. It is

recited at festivals and special functions and on

numerous other occasions. Every Muslim child is taught

it as soon as it is old enough to learn. It is usually

finished with an amin, the equivalent of the Christian

"amen", and some old handwritten texts of the quran

Qurčan actually insert the word at the end of a chapter

as part of the text. The importance of this chapter can

be seen from the following quote where it is singled out

as the quran Qurčan's most significant passage:

And We have bestowed on you the Seven Oft-Repeated

(verses) and the Exalted quran Qurčan. Surah 15.87

There are numerous references to this surah in the

traditional Hadith literature. Muhammad is recorded as

stating that the "seven oft-repeated" (sabaul mathani

saba ul-mathani) were the seven verses of the chapter

and that "the Exalted quran Qurčan" (quranal adhim

al-Qur'anal- Adhim) was also a title for the Surah

(Muwatta Imam Malik, p.37). Another popular title for it

is ummul quran Ummul-Qur'an, the "Mother of the quran

Qurčan". It is unique in that it is the only part of the

quran Qurčan where there is a human address to God.

Another tradition records Muhammad as stating very

emphatically that its recital is crucial to any time of

prayer:

He who does not recite Fatihat al-Kitab is not

credited with having observed prayer. (Sahih Muslim,

Vol.1, p.214).

Two other similar traditions record the Prophet as

personally defining this chapter as the most significant

in the quran Qurčan:

Shall I not teach you the most important Surah in the

quran Qurčan? He said it is "Praise be to Allah, the

Lord of the Worlds".

(Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6, p.490).

"All praise be to Allah, the Lord of the Universe" is

the epitome or basis of the quran Qurčan, the epitome or

basis of the Book, and the seven oft-repeated verses.

(Sunan Abu Dawud, Vol.1, p.382).

During the official prayers recited five times daily

it is only the Imam, the leader, who recites the actual

prayers including this Surah. Nonetheless another

tradition states that all Muslims should deliberately

recite the amin at the end of it. Muhammad himself

related that the angels of heaven themselves do so and

that every Muslim who coincided his amin with theirs

would have all his sins forgiven (Sahih al-Bukhari,

Vol.1, p.416). The importance of the opening chapter to

the Muslims of the world can hardly be over-emphasised.

Another short but very important chapter is known as

Suratul-Ikhlas (the "Chapter of Purity") and it reads as

follows:

In the name of Allah, the Compassionate, the

Merciful. Say: He is Allah, the One; Allah, the Eternal

One; He does not beget, nor is he begotten, and like

unto him there is not one.

(Surah 112. 1-4).

The unity of Allah is the central theme of the quran

Qurčan and his sole and absolute Lordship over the

Universe is constantly emphasised. This is usually done

in opposition to the pagan idolatry of Muhammad's fellow

countrymen but it is also levelled against the Christian

belief in Jesus as the begotten Son of God. Muslims

today regularly employ it in apologetic literature

against Christianity and it is perhaps a defiant summary

of the basic polemic of Islam against other faiths.

Muhammad is recorded as saying that "this Surah is

equal to one-third of the quran Qurčan" (Sahih

al-Bukhari, Vol.6, p.494) and it is regularly recited as

Muslims believe this is the same as reciting a third of

the whole book. The Prophet once enquired of his

companions whether any of them was capable of reciting

one-third of it in one night and when they all expressed

surprise he again stated that this Surah "is equivalent

to a third of the quran Qurčan" (Sahih Muslim, Vol.2,

p.387). Another tradition records him one day hearing a

man reciting this chapter and saying that he was assured

of Paradise (Muwatta Imam Malik, p.99). One of his

companions also heard another Muslim reciting it

repeatedly one night and, taking the chapter to be a

very short one and seeing no point himself in reciting

it continuously, he objected to Muhammad but was

likewise told that it was by Allah's direction a third

of the book (Sunan Abu Dawud, Vol.1, p.383).

Only one other Surah is regarded with the same awe as

these two and that is the 36th chapter of the quran

Qurčan known as Suratu-Ya-Sin after the two letters ya

and sin appearing as typically unexplained letters at

its beginning. Muslim calligraphers have often selected

its first few verses as a subject for intricate artistic

skills as it has often been taught that this Surah is

the heart of the quran Qurčan and that Allah writes in

exchange for anyone who recites it the reward of reading

the whole quran Qurčan ten times. It is accordingly

regularly found in Muslim prayer booklets, very often

being printed by itself as a separate booklet.

Typical Cliches and Other Significant Passage

The quran Qurčan is a book full of sharp cliches

which add to its rhythmic character. Perhaps the most

obvious of these are the names given to Allah (usually

two) after a verse concentrating on him or his actions.

For example he is described as

Allaaha-Tawwaabaan-Rahiimaan, "Allah the Oft-Returning,

the Merciful" (Surah 4.64) at the end of a passage

declaring that unbelievers would have found Allah so if

they had only come to the Prophet after first disobeying

him and asking forgiveness with him likewise praying for

their forgiveness.

Another passage states that Allah raised Jesus up to

himself when the Jews sought to kill him, concluding wa

kaana Allaahu aziizaan Aziizaan Hakiimaan, "And Allah

is the Mighty, the Wise" (Surah 4.158). These names of

Allah were in time compiled into ninety-nine in all.

There are a few verses in the quran Qurčan of

exceptional character and one of the most well-known is

the ayatul-kursi, the "Throne verse". It is perhaps the

most eloquent declaration in the book of Allah's

universal sovereignty over his creation and starts and

finishes with two typical names indicative of his

surpassing power and glory. It stands out by itself in

the longest chapter of the quran Qurčan and reads as

follows:

Allah! There is no god but He, the Living, the

Everlasting. Neither slumber nor sleep seize Him. To Him

is everything that is in the heavens or on the earth.

Who is there that can intercede with Him except as He

permits. He knows what lies before them and what is

after them and they will comprehend nothing of His

knowledge save as He wills. His Throne covers the

heavens and the earth and He has no tiredness in

preserving them. He is the Most-High, the Exalted. Surah

2.255.

Although the Suratul-Fatihah is regarded as the most

important chapter in the quran Qurčan this particular

verse was said by Muhammad to be the foremost in the

book:

Ubayy b. kab Ka b said: The Apostle of Allah (may

peace be upon him) said: Abu al-Mundhir, which verse of

Allah's book that you have is the greatest? I replied:

Allah and his Apostle know best. He said: Abu

al-Mundhir, which verse of Allah's book that you have is

greatest? I said: Allah, there is no god but He, the

Living, the Eternal. Thereupon he struck me on the

breast and said: May knowledge be pleasant for you, Abu

al-Mundhir.

(Sunan Abu Dawud, Vol.1, p.383).

Another very striking verse in a passage from the

Medinan period of Muhammad's prophetic mission also

stands out. This time, although Allah is again its

central theme, the text moves into the mystical realm in

its description of his glory and it is accordingly

highly esteemed by the Sufis, the mystics of Islam. It

reads:

Allah is the light of the heavens and the earth. The

parable of His Light is as if there were a Niche and

within it a Lamp; the Lamp enclosed in a Glass; the

Glass as it were a Brilliant Star, lit from a blessed

tree, an Olive neither of the East nor the West, whose

Oil is well-nigh luminous though fire has scarce touched

it: Light upon Light! Allah guides whom He wills to His

light and Allah sets forth parables for men, and Allah

knows all things. Surah 24.35.

Mention should be made of the last two surahs of the

quran Qurčan. These are, like the opening chapter, very

short and once again the Muslim worshipper is the

speaker although on this occasion he does not address

his praise to Allah but recites an incantation seeking

protection firstly from the Lord of the dawn against the

mischief of talismans, the darkness, those who practise

secret spells and those who practise magical envy such

as the well-known "Evil-Eye" (Surah 113. 1-5). This

chapter is known as Suratul-Falaq ("The Dawn") while the

second is known as Suratul-Nas ("Mankind") as Allah is

here described as the Lord of mankind from whom

protection is sought against the mischief of the

Whisperers among both devils and men (Surah 114. 1-6).

Ayishah, one of Muhammad's wives, related that these

two stories had a special significance and that he

regularly used them. Every night he used to cup his

hands together and blow over them after reciting both

surahs as well as Suratul-Ikhlas. He would then rub his

hands over whatever parts of his body he could reach,

starting with his head, face and the front of his body.

He used to do this three times. Whenever he was ill he

would recite them again and blow breath over his body.

Ayishah at such times also used to recite them over him

and rub his hands over his body hoping for its blessings

(Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol.6, p.495). One of his companions

recorded the following incident where Muhammad specially

recommended the recitation of these two Surahs as a form

of protection:

`Uqbah b. `Amir said: While I was travelling with the

Apostle of Allah (may peace be upon him) between

Al-Juhfah and al-Abwa, a wind and intense darkness

enveloped us, whereupon the Apostle of Allah (may peace

be upon him) began to seek refuge in Allah, reciting: "I

seek refuge in the Lord of the dawn" and "I seek refuge

in the Lord of men". He then said: `Uqbah, use them when

seeking refuge in Allah, for no one can use anything to

compare with them for the purpose. He said: I heard him

reciting them when he led the people in prayer.

(Sunan Abu Dawud, Vol.1, p.383).

There is great merit to the Muslim in reciting any

part of the quran Qurčan but these surahs and passages

have an exceptional value and the Prophet's own

endorsement of each of them in turn has secured their

prominence and incessant recitation whenever

appropriate.

4. The Meccan and Medinan Surahs

The Style and Character or the Two Periods

One of the problems confronting any student of the

quran Qurčan is the fact that the book not only has no

chronological sequence but that the various surahs

themselves are often composed of passages from both the

Meccan and Medinan periods of Muhammad's mission.

Nonetheless there is a clear distinction between them

which can be discerned in the nature of the two phases.

While in Mecca Muhammad saw himself primarily as a

warner to draw his people away from idolatry and the

surahs from this time are generally prophetic and

exhortative in character. In Medina, however, Muhammad

was the leader of a community and the surahs from this

period in contrast to the Meccan passages are often

cumbersome and legalistic in content and style.

The Meccan surahs concentrate on the issues which

first impressed themselves upon Muhammad, in particular

the waywardness of his own people, the judgment to come,

and the destiny of all men to heaven or hell. Perhaps

the most striking issue here is al-Yaum, "the Day", the

Great Day of Judgment to come. The quran Qurčan

concentrates all its warnings around this awful event.

Graphic language is used to describe it. For example it

is described as "totally overwhelming" (Surah 88.1),

hell itself will be brought face-to-face with mankind on

it (Surah 89.23) and no soul shall have power to help

another for the Command, that day, shall belong to Allah

alone (Surah 82.19). The destiny of unbelievers shall be

horrific:

Some faces on that Day will be humiliated, labouring,

exhausted; roasting in a blazing fire, drinking from a

boiling hot spring; no food for them but a thorny

cactus, neither nourishing nor relieving hunger. Surah

88. 2-7.

On the other hand believers will be blessed that Day.

They will laugh at the unbelievers (Surah 83.34), their

surroundings will be as comfortable as they could wish

with a light of beauty and joy over them (Surah 76.11),

they will be lavishly adorned and will drink of a pure

and holy wine (Surah 76.21). Much of the quranic

Qurčanic concept of heaven follows Biblical principles

but the emphasis seems to be on the pleasure and ease of

the believer's circumstances rather than the renewed

knowledge of God's perfect character within them. In

contrast to the terrors of hell in the passage quoted

the text says of the inhabitants of paradise:

Other faces will be joyful, pleased with their

efforts, in a sublime Garden, hearing no vain-talk.

Therein will be a bubbling fountain, therein couches

raised up and goblets set out, cushions arrayed and

carpets spread out. Surah 88. 8-16.

In all this the Prophet is reminded that he is only a

warner for those who are ready to fear the Day (Surah

79.45). Yet, once he became established in Medina, the

tone began to change. In Mecca the quran Qurčan spoke

directly to Muhammad or to his countrymen generally, but

in Medina one finds the majority of passages addressing

the community of believers with the introduction Yaa

ayyuhallathiina aamanuu aa manuu-"O you who truly

believe". What follows is often of a legislative nature

and most of the laws of Islam, the shariah shari ah, are

derived from these sections. The concern here is chiefly

the social ethics of the Muslim ummah, the conduct of

campaigns and battles, general customs and behaviour and

religious scruples regarding such things as marriages

and deaths.

The Medinan surahs deal with the abolition of usury

and interest (Surah 2.278), the laws of inheritance

(Surah 4. 11-12), the prohibited degrees of relationship

(Surah 4.23), the property of orphans (Surah 4. 6-10),

the prohibitions on wine and gambling (Surah 5. 93-94)

and the like.

One of the great themes of these surahs is the person

of the Prophet of Islam, Muhammad himself. While he is

often addressed directly in the Meccan surahs, his own

position is seen to be no more than to be a communicator

of Allah's revelations. Here, however, he comes to the

fore and one of the great injunctions in these later

passages is to obey Allah and his Messenger (Surah

48.17) as loyalty to the one is seen to be inseparable

from faithfulness to the other.

In the Medinan surahs passages dealing with the Great

Day and the destiny of mankind give way to new

revelations dealing with the personal concerns of the

Prophet's private life. For example he is given a

special licence to take to himself and marry any

believing woman who is willing to devote herself to

him-a permission expressly granted to him and not to

believers generally "so that there should be no

difficulty for you" (Surah 33.50). In the next verse of

a book said to be eternal and of uncreated speech

preserved on a special tablet in heaven, he is told that

he can choose for himself which of his wives he would

like to be with at any time and that he would be doing

no wrong if he preferred one over another and showed

partiality to her. Believers are also commanded to send

their blessings on him and to salute him with all

respect because Allah and all his angels do so (Surah

33.56). Furthermore those who annoy and irritate him

(and, perforce, Allah as well) will be cursed by Allah

in both this world and the next (Surah 33.57). His

companions are even given strict details regarding

etiquette to be observed when approaching his chambers:

O you who truly believe! Do not enter the houses of

the Prophet until leave is given you for a meal and then

without you watching for its hour. But when you are

invited, then enter, and when you have had the meal,

disperse without lingering for idle talk for this

irritates the Prophet and he is ashamed before you-but

Allah is not ashamed to tell you the truth! Surah 33.53

The arrangement of the chapters of the quran Qurčan,

whereby the early Meccan surahs are placed at the end of

the book and the Medinan surahs at the beginning, is

confusing and the casual reader will miss the clear

transition but it is there-the sharp awareness of

eternal issues giving way to concerns of a more

practical, immediate and earthly nature.

quran

The Theory of Abrogation in the Qurčan

One of the unique features of the quran Qurčan is its

teaching that Allah can abrogate earlier teachings in

his Scriptures by substituting something else in their

place. This applies not only to the Scriptures prior to

Islam but to the quran Qurčan itself. There is a clear

doctrine in the book that some of its earlier verses are

cancelled by later revelations. Muhammad always saw

Allah as the absolute sovereign of the universe and the

idea that he could alter his commands and replace them

obviously appeared to be in harmony with his supreme

rule and he saw no reason to question it. The most

prominent verse in the quran Qurčan setting forth the

doctrine reads:

We do not abrogate a verse or let it be forgotten

without bringing a better or similar one. Do you not

know that Allah has power over all things? Surah 2.106

In the early days of Islam there was no dispute about

the meaning of this text. It was universally accepted

that it meant that certain verses and passages of the

quran Qurčan could be substituted by later ones and

lists were drawn up of texts abrogated by later

revelations. For example in one place the quran Qurčan

teaches that the drinking of wine can have both good and

bad effects (Surah 2.219) and when Muhammad first

established himself as the ruler of the Muslim community

at Medina his followers were told not to come to prayers

in a drunken state (Surah 4.43). Later, however, the

consumption of alcohol was abolished altogether (Surah

5. 93-94).

Two of the greatest of the early commentators of the

quran Qurčan, Baidawi and Zamakhshari, attempted to

interpret the purpose of this facet of quranic Qurčanic

revelation in the context of a definite substitution of

one passage by another. Zamakhshari taught that Surah

2.106 was revealed to counter the objections of the

pagan Arabs that Muhammad at times would command his

followers to do a certain thing and would later forbid

it and command the opposite. He believed, unlike other

commentators who held that the abrogated verses remained

in the quran Qurčan, that Allah expressly removes

(azala) one passage to insert another. He commands the

angel of communication, Jibril, to announce that one

passage is cancelled either by its abolition or by its

replacement with another passage.

Baidawi likewise taught that the mansukh verse, the

"abrogated" text, became of no effect. It was no longer

a pious act to recite it and no law based on it could be

valid any longer. He argued that the naskh verses which

came in the place of the cancelled texts were inserted

as each occasion required. Laws are formulated by Allah

for the good of mankind and as the needs and

circumstances change with time and the individual it

becomes necessary for the rules that regulate them to be

adapted as well. What may be beneficial at one time can

be harmful at another. So Allah reserves to himself the

right to alter his revelations as he pleases.

It is not possible to determine which texts, if any,

were taken out of the quran Qurčan once they were

abrogated but another typical example of a new passage

overruling an earlier one due to force of circumstances

is found in the context of praying and reading the quran

Qurčan at night. At Mecca the practice went on into the

early hours of the morning when the early Muslims were

not so pressed with communal affairs. In one of the

earliest passages to be revealed they were commanded to

pray for approximately half of each night and to recite

the quran Qurčan at the same time (Surah 73. 2-4). Once

they were settled in Medina, however, the daily concerns

of attending to the needs of the growing Muslim

community made it very hard for them to maintain long

hours awake at night and so the command was relaxed. The

same Surah goes on in a later passage to say that, while

Allah is aware that they stand up to half the night in

prayer, he knows they cannot keep count of the time they

are so engaged and so he only expects them to read the

quran Qurčan and pray for as much as may be comfortable

to them. He knows that some are ill and others are weary

travellers and that yet others are fighting in campaigns

(Surah 73.20). Thus the fixed injunctions of the earlier

passage were abrogated.

There are other verses in the quran Qurčan clearly

teaching that Allah can change his revelations and

substitute one for another as he pleases:

When We exchange a verse in place of another verse,

and Allah knows best what he is sending down, they say

"You are but a forger!", but most of them have no

understanding.

Surah 16.101

Allah abolishes and establishes what he pleases for

with him is the Mother of the Book. Surah 13.39

The doctrine of abrogation of actual verses of the

quran Qurčan was clearly taught and indeed fixed by the

fuqaha, the early jurists of Islam. Nonetheless modern

Muslim scholars, chastened by the suggestion that the

quran Qurčan is not a perfect scripture if some of its

texts have been superseded by others, or at worse

actually removed from the book, attempt to prove that

the quran Qurčan is really teaching that what Allah does

is to abrogate some of the previous scriptures (each of

which is known in the quran Qurčan as a kitab, a "book")

and not passages of the quran Qurčan as such.

This line of reasoning cannot be accepted as the

quran Qurčan never says that a kitab is abrogated in its

entirety but rather that Allah substitutes one ayah for

another ayah (Surah 16.101). The word often means

"signs" (such as the miracles of Jesus) but throughout

the quran Qurčan it also refers to actual verses of the

book itself. Allah has sent down his revelations (or

verses - ayat) to Muhammad which none but the perverse

reject (Surah 2.99). It was the practice of cancelling

verses or overruling their contents with later texts

that made the Prophet's opponents charge him with being

a forger as this seemed to be a convenient way to

explain changes in the actual text of the quran Qurčan

itself.

In Surah 2.106 the text speaks not only of Allah's

revelations being abrogated but also being forgotten by

his power-this could hardly refer to previous scriptures

which were well-known and preserved throughout the known

world in thousands of manuscripts. It could only refer

to actual verses of the quran Qurčan which had come to

be neglected and forgotten by Muhammad and his

companions over a period of time.

|